Em um novo livro de memórias, Tariq Ali relata seu trabalho e ativismo no fim da era da Guerra Fria e na era da globalização neoliberal. Ele falou com a Jacobin sobre o que significa ser um anti-imperialista em um mundo transformado.

Uma entrevista com

Tariq Ali

|

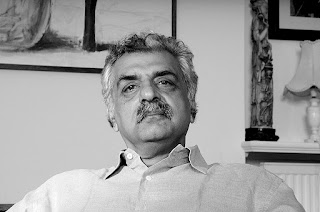

Tariq Ali em sua casa em Londres em 15 de julho de 2003. (Cambridge Jones / Getty Images) |

Entrevista por

Stathis Kouvelakis

O novo livro de Tariq Ali, You Can’t Please All, é uma continuação de sua "autobiografia dos anos 60", Street-Fighting Years. Essas novas memórias que cobrem o período de 1980 a 2024 refletem a atividade prolífica do autor e abrangem uma gama excepcionalmente ampla de tópicos. Eles abordam tudo, da América Latina ao Paquistão, Perestroika, Grã-Bretanha sob Margaret Thatcher e depois, o histórico familiar do autor, intervenções culturais na TV e no palco, críquete na era pós-colonial, uma leitura política de Dom Quixote e muito mais.

O relato de Ali testemunha a profunda mudança que o mundo viu desde o recuo global pós-1968. Refletindo sobre sua própria trajetória, ele explora as maneiras pelas quais revolucionários, movimentos de massa e intelectuais responderam a uma nova situação.

Entrevistado por Stathis Kouvelakis para Jacobin, Ali se concentra no fio condutor de sua vida política: o anti-imperialismo e seu significado no período pós-Guerra Fria do capitalismo neoliberal globalizado.

Anti-imperialismo e a esquerda, dos anos 1960 até hoje

Stathis Kouvelakis

O anti-imperialismo dominou sua vida inteira, desde sua primeira ação política — uma manifestação nas ruas de Lahore após o assassinato de Patrice Lumumba em 1961 — até os anos 2000, quando, após um longo período dedicado principalmente ao trabalho cultural, você retornou à política ativa em torno da política anti-guerra e anti-imperialista. Você sempre foi um internacionalista convicto, mas seu internacionalismo tem uma ponta definitivamente anti-imperialista, certo?

Tariq Ali

Eu acho que isso é verdade. Morando no Paquistão, eu era completamente obcecado desde muito jovem em ler todas as revistas que chegavam em casa. Eram principalmente revistas comunistas dos Estados Unidos — Masses and Mainstream, Monthly Review — e depois da Grã-Bretanha, New Statesman, Labour Monthly e só muito tarde a New Left Review. Eu as lia porque estava interessado na situação pós-colonial. No Paquistão, estávamos passando por uma fase pós-colonial, que não parecia diferente do que era nos últimos dias do imperialismo britânico. Tudo era comandado pelos britânicos, que então entregavam aos americanos.

Quando li sobre a morte de Lumumba, fiquei realmente furioso. Convocamos uma reunião na faculdade e eu disse: "Não podemos deixar de sair às ruas". Mas, de acordo com uma antiga lei imperial britânica, era punível com prisão pesada se manifestar com mais de cinco pessoas juntas. Mas decidimos que faríamos isso e cerca de duzentas apareceram. Explicamos quem era Lumumba e eles disseram: "Estamos marchando para o consulado dos EUA porque essas são as pessoas que o mataram". Um cara perguntou: "Há alguma prova?" O lugar inteiro caiu na gargalhada. Ninguém duvidou que fossem os americanos. Voltamos da embaixada e nos sentimos tão fortes e corajosos que começamos a gritar slogans contra a ditadura militar no Paquistão. Fizemos isso e o país ficou perplexo: Quem são essas crianças malucas? Quando li sobre a morte de Patrice Lumumba, fiquei realmente furioso. Convocamos uma reunião na faculdade, e eu disse: "Não podemos deixar de sair às ruas".

Foi uma manifestação memorável, porque pegou todo mundo de surpresa. Não houve uma única manifestação sobre Lumumba no Ocidente ou na Índia, em países onde seria legal, com grandes partidos comunistas. Ainda encontro pessoas que dizem: "Lembro-me da manifestação de Lumumba em Lahore". Eu digo: "Você estava nela?" Eles dizem: "Sim, sim, claro..." Então, parece que agora o tamanho da manifestação aumentou para 50.000 pessoas! [risos]

Então, a Revolução Chinesa estava acontecendo. Todo o movimento progressista de esquerda — sindicatos e movimentos camponeses na vanguarda — falava constantemente sobre a China. Quando eu era muito jovem, meus pais me levaram para a reunião do Primeiro de Maio e a única conversa era sobre a China: o slogan gritado era: "Vamos pegar o caminho chinês, camaradas".

Então, toda a noção de luta e revolução surgiu muito cedo para mim, e não teria acontecido se eu tivesse crescido em uma parte diferente da minha própria família. Foram meus pais sendo comunistas e pessoas daquele meio vindo regularmente à nossa casa — poetas, radicais — que me impulsionaram nesse caminho. Lembro-me de quando os franceses foram derrotados em Điện Biên Phủ, pessoas apolíticas estavam comemorando. Um primo da minha mãe, que era produtor de cinema, ligou para ela para comemorar e disse: "Meu filho nasceu hoje, eu o chamei de Ho Chi Minh". Minha mãe disse: "Se até essas pessoas estão comemorando Điện Biên Phủ, talvez não tenhamos tanto azar neste país". Era um sentimento semi-nacionalista, mas firmemente anti-europeu e anti-americano anti-imperialista entre as pessoas em geral. Toda a noção de luta e revolução surgiu muito cedo para mim, e não teria acontecido se eu tivesse crescido em uma parte diferente da minha própria família.

Stathis Kouvelakis

O que é notável no seu caso, vindo do Sul Global, não é que você se tornou um anti-imperialista nas décadas de 1960 e 1970, mas que você permaneceu assim. Desde que você reiniciou a atividade política no mundo após a queda da União Soviética, você tem feito campanha contra as novas guerras imperialistas, agindo e se conectando com vários experimentos, particularmente na América Latina, resistindo ao imperialismo americano. Muitos na esquerda permaneceram opostos ao neoliberalismo, mas abandonaram o anti-imperialismo.

Tariq Ali

Há uma contradição interessante aqui. Eu me juntei à Quarta Internacional [FI, o que era então conhecido como "Secretariado Unido"] porque era anti-imperialista e internacionalista, e essas eram suas características mais atraentes. Fiquei bastante chocado quando eles começaram a se afastar disso.

Eu me lembro de encontrar Daniel Bensaïd em Paris em algum café, e ele disse: "O quadragésimo aniversário de 1968 está chegando, o que devemos fazer? Você sempre tem boas ideias sobre como fazer grandes celebrações.” Eu disse, “Daniel, o internacionalismo, como o entendíamos antes, está apenas saindo de suas próprias fileiras. Em 1968, você estava renomeando as ruas do Quartier Latin de ‘Rua Heroica do Vietnã’.” Ele disse, “Ok, o que você está sugerindo?”

Eu disse, “Uma grande celebração das mudanças na América do Sul. Vamos chamar os zapatistas; não é impossível que Hugo Chávez venha. Teremos Evo [Morales] da Bolívia. Teremos a esquerda progressista neste país: há algumas pessoas que ainda estão persistindo. Eles não são revolucionários como nós éramos, mas são social-democratas de esquerda. Eles foram impulsionados ao poder por movimentos de massa.” Daniel disse, “É uma ideia muito interessante, mas não acho que ninguém entre os anticapitalistas a apoiará. Não é porque eles são hostis como tal, mas não os interessa.” Eu disse, “Isso é profundamente chocante.” Ele disse: "Posso imaginar que para alguém como você, é ainda mais chocante".

Ele sabia o que estava acontecendo, pois alguns outros camaradas dos velhos tempos estavam em negação.

Na época da Guerra do Iraque, tive uma grande discussão com Catherine Samary, da Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire. Claro, ela era contra a guerra. Mas perguntei a ela: "Como você explica o fato de que em todos os grandes países da Europa, vocês tiveram gigantescas manifestações antiguerra [em 15 de fevereiro de 2003]; milhões em Londres, Roma e Madri, até os alemães conseguiram 100.000. Você, na França, não conseguiu nada".

Stathis Kouvelakis

Mas houve manifestações: em Paris, os números foram semelhantes aos da Alemanha.

Mas houve manifestações: em Paris, os números foram semelhantes aos da Alemanha.

Tariq Ali

Eles eram comparativamente pequenos. O argumento de Catherine era que [o então presidente] Jacques Chirac se opôs à guerra, e é por isso que as pessoas se sentiam representadas. Eu disse: "Mas espere aí. Charles de Gaulle se opôs à Guerra do Vietnã. Isso não o impediu. É um problema estrutural profundo e fundamental no que aconteceu com a intelligentsia francesa e a esquerda francesa." Um pouco mais tarde, quando a edição francesa do meu livro sobre a Guerra do Iraque [Bush à Babylone: La Recolonisation de l'Iraq] saiu com La Fabrique, eu estava indo com Éric Hazan para livrarias em Paris e alguns outros lugares para dar palestras. Em um evento, eu disse: "Tenho a sensação de que uma parte da intelligentsia francesa, particularmente em torno do Parti Socialiste e dos liberais, realmente gostaria de ter feito parte desta guerra." Éric me interrompeu e disse: "Ele está completamente certo sobre isso." A Grã-Bretanha é o único país onde a Stop the War Coalition, mesmo em tempos ruins, sobreviveu. Não a deixamos afundar.

A evolução na França foi muito decepcionante. Tínhamos uma fé enorme naquele grupo [a Ligue Communiste, mais tarde a Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire] e seu élan, nas décadas de 1960 e 1970. É um pouco irônico que a ala "capitalista de estado" do movimento trotskista [o Partido Socialista dos Trabalhadores Britânico (SWP) e sua rede internacional, a Tendência Socialista Internacional (IST)] tenha se mostrado muito mais afiada e muito melhor, na Iugoslávia, no Iraque e agora na Ucrânia. Eles se opuseram fortemente à OTAN e aos EUA. Um dos motivos pelos quais costumávamos criticar o grupo IST era por causa de sua falta de internacionalismo.

Mas se você olhar agora, são as correntes mandelistas que foram consideradas deficientes e meio que desapareceram. Enquanto isso, sem o punhado de trotskistas do SWP como Lindsey German e John Rees, não poderíamos ter construído a campanha antiguerra. A Grã-Bretanha é o único país do mundo onde a Stop the War Coalition, mesmo em tempos ruins, sobreviveu. Não deixamos isso ir por água abaixo.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Obviamente, há uma relação entre essa persistência e o tamanho do movimento em apoio à Palestina na Grã-Bretanha.

Tariq Ali

Sem dúvida. Sobre a Palestina, tínhamos pelo menos uma manifestação por ano, então o movimento progressista britânico estava pronto quando chegou. Essas são as pessoas que organizam as manifestações da Palestina, depois a Campanha de Solidariedade à Palestina. Eles vieram e foi fantástico, ficou cada vez maior. Eu os avisei que mais cedo ou mais tarde isso iria por água abaixo: temos que pensar em outras ações. E então outras ações começaram espontaneamente por uma nova geração, novata na política, que nunca esperávamos. Eles não são atraídos por pequenos grupos — a velha maneira de fazer as coisas.

Aqui chegamos ao problema, que é que enquanto na política francesa você tem Jean-Luc Mélenchon, aqui [na Grã-Bretanha] não há ninguém além de Jeremy Corbyn. Suas fraquezas como líder de esquerda vêm à tona. Ele é fisgado pelo trabalhismo mesmo quando é expulso dele.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Você poderia comentar a seguinte declaração feita por outro líder trotskista, Michel Raptis, também conhecido como Pablo. Perto do fim de sua vida, ele disse ao revolucionário e teórico mexicano Adolfo Gilly: "O significado mais profundo do século XX foi esse imenso movimento pela libertação das colônias, dos povos oprimidos e das mulheres, não a revolução do proletariado, que era nosso mito e nosso Deus". Você concorda?

Tariq Ali

Em parte. É isso que Ernest Mandel costumava chamar às vezes — em relação ao que ele chamava de "centristas" — de adoração de fatos consumados.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Mas, como você diz em seu livro, ele estava acusando a New Left Review de fazer isso...

Tariq Ali

Sim, e ele estava certo. No entanto, em Portugal, chegamos muito perto de um desfecho revolucionário, na minha opinião, muito mais perto do que na França em maio e junho de 1968, porque lá o Partido Comunista Francês era um grande baluarte, enquanto em Portugal o Partido Comunista, gostemos ou não, estava do lado da extrema esquerda. Mas eles foram totalmente superados. Lembro-me de grandes manifestações de trabalhadores, soldados e camponeses em Portugal, onde o cântico era "Revolução, revolução, socialismo". Em Portugal, chegamos muito perto de um desfecho revolucionário, na minha opinião, muito mais perto do que na França em maio e junho de 1968.

Então Mário Soares, o líder social-democrata, veio e disse: "Sim, teremos socialismo. Mas queremos o socialismo da Europa Oriental? Não. Queremos o socialismo dos russos? Não. Então por que nosso querido camarada Álvaro Cunhal [secretário-geral do Partido Comunista Português] fala constantemente sobre a ditadura do proletariado? Nós nos livramos de uma ditadura, e eles querem trazer outra nesse modelo.” Cunhal nunca poderia responder a isso. Ideologicamente, fomos derrotados em Portugal.

Ernest [Mandel] ficou abalado porque estava muito animado, embora a FI tenha subestimado Portugal porque [Mandel] estava convencido de que a revolução iria estourar primeiro na Espanha. Vários de nós que conhecíamos melhor a Espanha, dissemos a ele: “Haverá um grande compromisso na Espanha.” Ele disse: “Você está errado. As tradições do POUM [Partido dos Trabalhadores da Unificação Marxista], do anarquismo etc... .” Os camaradas bascos [da ETA-VI], que eram muito afiados, disseram que a sucessão pós-[Francisco] Franco será boa porque seremos legais, mas nada mudará muito. Portugal pegou a FI completamente de surpresa.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Então, para você, o século XX ainda foi o século das oportunidades revolucionárias perdidas, mesmo na Europa ou nos países capitalistas avançados.

Tariq Ali

Sim, acho que foi esse o caso até 1975, a derrota da Revolução Portuguesa foi o fator decisivo. Fidel Castro sentiu fortemente que agora tínhamos sido derrotados pelas gerações vindouras, mas essa não era a sensação que tínhamos na Europa.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Mais do que o golpe no Chile?

Tariq Ali

O golpe no Chile teve, é claro, um grande impacto. Mas havia uma enorme simpatia pelo Chile, mesmo entre os círculos burgueses, não havia uma sensação de que a revolução tinha sido derrotada. Lembro-me de Hortensia Allende sendo recebida pelo então primeiro-ministro britânico e líder do Partido Trabalhista, Jim Callaghan, que a abraçou em público. Ela discursou na conferência do Partido Trabalhista dizendo: "O camarada Allende foi assassinado", e toda a conferência ficou em silêncio. Fidel Castro sentiu fortemente que agora tínhamos sido derrotados pelas gerações vindouras, mas essa não era a sensação que tínhamos na Europa. Na Europa, o teste crucial era Portugal, e os americanos sabiam disso. O dinheiro da OTAN foi despejado em Soares e seu partido [reformista].

Imperialismo hoje: Um império global americano?

Stathis Kouvelakis

Vamos agora para o mundo pós-1990. Sua posição é que há apenas um império global, o império dos EUA. Como você caracterizaria a China e a Rússia? Elas são potências imperialistas; elas precisam ser colocadas no mesmo plano que os EUA? Esta é a posição de toda uma parte da esquerda radical hoje, que faz um paralelo entre a situação atual e a configuração interimperialista do período pré-Primeira Guerra Mundial. As mesmas pessoas acrescentam que, ao pensar que um imperialismo é de longe o dominante, e portanto mais perigoso para qualquer governo progressista, você comete o pecado do "campismo".

Tariq Ali

Eu fui bem claro sobre esta questão em The Clash of Fundamentalisms. Quem foi o grande vencedor do colapso da União Soviética e da virada chinesa para o caminho capitalista? Foram os Estados Unidos. O capitalismo americano continuou sendo o capitalismo mais forte, não apenas militarmente, mas econômica e tecnologicamente. Não é por acaso que a Internet surgiu na costa oeste dos EUA, não na costa oeste da China. A dominação ideológica dos EUA era virtualmente incontestável. Tínhamos que desafiá-la, é claro, mas não seríamos capazes de fazer isso se parássemos de dizer que a América era uma potência imperial.

Não faz sentido dizer que, porque a União Soviética implodiu e a China se tornou capitalista, não há mais uma potência imperial. Eu era muito fortemente contra essa visão, mas as pessoas eram muito relutantes em contestá-la. Em conferências acadêmicas, quando eu falava sobre "imperialismo dos EUA", havia um leve tremor, significando que pensávamos que tínhamos perdido todo aquele mundo. Não, você não perdeu aquele mundo, você perdeu outro. Quando eu estava na União Soviética no final dos anos 1980 e início dos anos 1990, falando com intelectuais seniores do partido, o que os estava deixando loucos era que Mikhail Gorbachev não conseguia ver que eles seriam esmagados por esses bastardos a menos que tivéssemos algo. Yevgeny Primakov em particular temia que Gorbachev estivesse preparando uma capitulação. Em conferências acadêmicas, quando eu falava sobre "imperialismo dos EUA", havia um leve tremor: as pessoas pensavam que tínhamos perdido todo aquele mundo. Não, você não perdeu aquele mundo, você perdeu outro.

Minha visão sobre a China e a Rússia é que elas são essencialmente nacionalistas, que defenderão seu nacionalismo, ou soberania nacional, se você quiser chamar assim. Os russos disseram que isso inclui não ter a OTAN nos cercando, ou a OTAN tentando nos dividir em pedacinhos. E os chineses dizem coisas semelhantes. Deixe-nos em paz, não nos provoque com Taiwan. Os americanos poderiam ter feito isso, estava lá para eles agarrarem, mas fizeram exatamente o contrário.

Perry [Anderson] e eu tivemos essa discussão em particular e minha visão era que o debate entre Karl Kautsky e [Vladimir] Lenin sobre as contradições ultraimperialismo versus interimperialista parece ter sido resolvido em favor de Kautsky. Durante a maior parte do século XX, Lenin estava mais ou menos correto, mas agora, após a queda da União Soviética, parece que teremos um ultraimperialismo de alguma forma em que todas as potências europeias mais ou menos capitulariam. Não há dúvida de que eles vão revidar. Senti isso ainda mais fortemente agora, durante o ataque à Palestina.

Na década de 1990, os russos e os chineses estavam preparados para acompanhar o ultraimperialismo dos EUA e os europeus, mas eram muito grandes para serem engolidos como a Europa foi, especialmente a China. Houve um grande debate dentro dos círculos econômicos chineses sobre se eles deveriam simplesmente ceder ao modo neoliberal de ir para o capitalismo. Então, houve uma grande reação de dentro do Partido Comunista da China dizendo: "Não, não podemos ir assim, não podemos cometer o erro de Gorbachev". Deng Xiaoping aconselhou Gorbachev que a perestroika [reestruturação] é boa, mas você não pode fazer a perestroika corretamente a menos que se esqueça da glasnost [abertura e transparência]. De um ponto de vista puramente cínico, ele não estava tão errado. Na década de 1990, os russos e os chineses estavam preparados para acompanhar o ultraimperialismo dos EUA e os europeus, mas eram muito grandes para serem engolidos como a Europa foi, especialmente a China.

Toda a estratégia dos EUA e dos pensadores e especialistas militares que governam aquele país é que a única maneira de manter sua hegemonia é quebrar tudo em pequenos pedaços, para que nenhum país surja que possa desafiá-lo, até o fim da humanidade. É isso que os EUA têm feito onde quer que você olhe. Foi o que eles fizeram na Iugoslávia, embora sem pensar. [Bill] Clinton disse a uma audiência em alguma cidade americana que a guerra na Iugoslávia era do interesse dos EUA. E eles fizeram o mesmo no Oriente Médio: para quebrá-lo, dividir os três países que tinham enormes exércitos que ameaçavam Israel e a hegemonia americana na região.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Então você não vê a ascensão econômica e a expansão da China em escala global se transformando em um novo imperialismo.

Então você não vê a ascensão econômica e a expansão da China em escala global se transformando em um novo imperialismo.

Tariq Ali

Poderia, se os Estados Unidos os provocassem. Não nego essa possibilidade. Os americanos tinham dois grandes planos para desestabilizar a China: Tibete e Taiwan. O Tibete agora está integrado por um mega-influxo de migrantes chineses han. Eles fizeram isso também modernizando o Tibete e disponibilizando muitos empregos para os tibetanos. O resultado é bastante surpreendente: é uma operação clássica de estilo imperial, mas não como o que os britânicos fizeram quando tomaram um lugar como a Índia. Eles estão construindo infraestrutura, não apenas trens e coisas para rotas de suprimento.

Em relação a Taiwan, qualquer tentativa do Ocidente de encorajar quaisquer provocações pelo governo em Taipei dificilmente funcionará, já que o comércio entre as duas regiões é intenso e quaisquer aventuras armadas seriam totalmente contraproducentes para Taiwan e seus cidadãos. Então, como isso vai acontecer? É difícil prever. Mas se os americanos tentarem dividir a China em pequenas partes, os chineses podem fazer qualquer coisa. Eles não vão aceitar isso deitados. Toda a estratégia dos Estados Unidos e dos pensadores e especialistas militares que governam o país é que a única maneira de manter a hegemonia dos EUA é dividindo tudo em pequenos pedaços.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Vamos agora para a Ucrânia, outro desenvolvimento crucial dos últimos anos. Não há questão de apoiar o regime [Vladimir] Putin ou pensar que ele é de alguma forma amigável à esquerda. Presumo que você concorde com a análise de Susan Watkins sobre a guerra na Ucrânia, que a vê como uma combinação de três tipos de guerras. Inspirada pela análise de Mandel sobre a Segunda Guerra Mundial, ela a vê como uma guerra interimperialista, uma guerra nacional contra uma invasão estrangeira e uma guerra civil que afeta particularmente o Donbass. O elemento mais controverso aqui é provavelmente a dimensão interimperialista, o que significa a responsabilidade do imperialismo dos EUA em provocar esta guerra ao expandir constantemente a OTAN para o leste.

Tariq Ali

Isso nos traz de volta ao que esses camaradas soviéticos estavam me dizendo: que Gorbachev está dando tudo isso sem nem mesmo um tratado escrito, que semicapitulações anteriores ou o que quer que seja sempre tiveram um tratado, e os alemães estavam preparados até para oferecer um. Os americanos não estavam. Eles deram garantias verbais: "nem uma polegada para o leste", como explicado no livro de Mary E. Sarotte. Ela é uma liberal de direita, mas seu livro dá um relato sólido de como os americanos operaram e o que eles fizeram desde o início, quando Gorbachev perguntou suavemente: "O que ganhamos em troca por entregar a Alemanha Oriental a você?" Ele recebeu uma garantia dos americanos, nem um passo para o leste com a OTAN. E Gorbachev acreditou. Isso deveria ter sido consagrado em um tratado — que poderia ter sido desconsiderado, é claro, mas ainda assim, estaria lá e teria alguma base legal.

Então eles começaram a mover a OTAN regularmente [para o leste] até desembarcarem na Ucrânia. William J. Burns, que agora é chefe da CIA [Agência Central de Inteligência], foi embaixador na Rússia entre 2005 e 2008. Quando voltou aos Estados Unidos, escreveu um artigo para Condoleezza Rice, [então secretária de Estado], dizendo muito claramente que a única coisa que não deveríamos provocá-los, que eles consideram uma linha vermelha, é incorporar a Ucrânia à OTAN. Agora, é claro, ele diz: "Eu os avisei em particular e estava certo."

Pessoalmente, não achei que Putin invadiria. Ele pegou todo mundo de surpresa. Claro, nós o criticamos fortemente e ele deveria sair. Mas a única maneira agora é sair [da guerra] por meio de negociações. Um de seus principais conselheiros disse a um amigo meu: "Putin manteve isso em segredo total. Mas, quando perguntei mais tarde sobre as crescentes baixas, etc., ele disse: 'Não seja tão crítico comigo. Somos a última geração que poderia enfrentar os americanos. Se eu não tivesse feito isso, a próxima geração nunca teria feito. Eles meio que vivem naquele mundo.”

Stathis Kouvelakis

Como você responde a um argumento moral que tem alguma aceitação, mesmo na esquerda: se os ucranianos querem se juntar à OTAN e fazer parte do Ocidente, por que deveríamos negar a eles o direito de fazê-lo? Isso não iria contra a noção de que eles têm agência e reproduzem um tipo de atitude colonial em relação aos ucranianos? Alguns sugerem que esse é o pecado da esquerda radical ocidental, que desconsidera os povos do Leste Europeu e não leva a sério seu desejo de se livrar da dominação russa.

Como você responde a um argumento moral que tem alguma aceitação, mesmo na esquerda: se os ucranianos querem se juntar à OTAN e fazer parte do Ocidente, por que deveríamos negar a eles o direito de fazê-lo? Isso não iria contra a noção de que eles têm agência e reproduzem um tipo de atitude colonial em relação aos ucranianos? Alguns sugerem que esse é o pecado da esquerda radical ocidental, que desconsidera os povos do Leste Europeu e não leva a sério seu desejo de se livrar da dominação russa.

Tariq Ali

Minha resposta é que as últimas eleições na Ucrânia antes da "revolução Euromaidan" retornaram um candidato abertamente pró-Rússia, Viktor Yanukovych. Esse presidente foi removido por uma "revolução colorida" americana, ou seja, uma mudança de regime que eles organizaram. Quem acredita que eles apoiariam algo como uma democracia genuína? Putin destruiu suas próprias chances, porque mesmo pessoas que eram muito pró-Rússia não podem ter nada a ver com ele agora. Os chineses estão falando sério em pelo menos rejeitar os planos americanos. Mas não penso isso do Sul Global como tal.

Então, é uma bagunça. Sou a favor, em geral, de ter referendos, mas vamos fazê-los abertamente. Não vamos ter nenhuma presença militar naquele país e deixar a ala fascista do [exército ucraniano] ser completamente desarmada. Caso contrário, como você pode ter as condições adequadas para um referendo? Os ucranianos podem então votar na [OTAN], o que duvido, já que muitos relatórios e artigos que Volodymyr Ishchenko está escrevendo indicam uma crescente insatisfação.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Há muita conversa sobre a ascensão do Sul Global como um ator independente no cenário global. Isso foi confirmado pela divisão Norte-Sul que vimos tanto na questão da Ucrânia quanto na Palestina. Isso não é homogêneo — a Índia de Narendra Modi, por exemplo, se recusou a aplicar sanções contra a Rússia, mas é muito pró-Israel. No geral, você acha que estamos caminhando para um mundo multipolar? Se sim, há algo positivo nessa mudança, apesar do fato de que todas essas potências emergentes no Sul Global são apenas países capitalistas?

Há muita conversa sobre a ascensão do Sul Global como um ator independente no cenário global. Isso foi confirmado pela divisão Norte-Sul que vimos tanto na questão da Ucrânia quanto na Palestina. Isso não é homogêneo — a Índia de Narendra Modi, por exemplo, se recusou a aplicar sanções contra a Rússia, mas é muito pró-Israel. No geral, você acha que estamos caminhando para um mundo multipolar? Se sim, há algo positivo nessa mudança, apesar do fato de que todas essas potências emergentes no Sul Global são apenas países capitalistas?

Tariq Ali

Eu diria que é uma tentativa de se mover para um mundo multipolar que nunca teria acontecido sem os chineses. É um sinal de que os chineses estão falando sério em pelo menos rejeitar os planos americanos. Mas não penso assim do Sul Global como tal. Eles podem obviamente resistir na Palestina, pois é tão flagrante o que os americanos e o Ocidente estão fazendo. Mas a noção de que eles fariam isso em tudo... duvido muito. A maioria das forças burguesas nesses países pode ser comprada. Não é tanto sobre ideologia, mas sobre quem paga mais dinheiro. É o mesmo com o Paquistão. A Índia é obviamente diferente, mas mesmo no Brasil alguma pressão foi exercida sobre [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] para recuar de sua posição inicial, que era muito fortemente contra os Estados Unidos e em apoio aos palestinos.

Lula costumava dizer: "Eles me tomaram por um idiota". Uma vez ele foi enganado por Barack Obama, que o bajulou e ele caiu na gargalhada, ele disse: "Isso nunca mais vai acontecer". Não é algo pessoal. É interesse americano, apoio dos EUA a Jair Bolsonaro e envolvimento no golpe parlamentar contra Dilma Rousseff. Então, ele não voltou atrás, mas tem brincado com eles. Ele também está nervoso que os militares ainda estejam infectados com Bolsonaro.

Eu acho que cada país está jogando as coisas de acordo com seus próprios interesses. Não há um tema predominante de oposição aos Estados Unidos. Tivemos uma versão melhor disso na década de 1960 com a Conferência de Bandung.

Stathis Kouvelakis

Sim, mas havia um projeto social diferente lá.

Sim, mas havia um projeto social diferente lá.

Tariq Ali

Concordo, não há nenhum projeto social agora, e é por isso que é tão fácil desmantelá-lo se os americanos quisessem fazê-lo.

Concordo, não há nenhum projeto social agora, e é por isso que é tão fácil desmantelá-lo se os americanos quisessem fazê-lo.

A causa palestina: um novo Vietnã?

Stathis Kouvelakis

O movimento em apoio à Palestina tem sido, eu acho, o desenvolvimento mais esperançoso no Ocidente no período recente. Podemos estabelecer um paralelo entre isso e o movimento contra a Guerra do Vietnã na década de 1960, do qual você foi um protagonista? Você acha que o apoio quase unânime dos governos ocidentais ao genocídio em Gaza de alguma forma sairá pela culatra, provocando uma crise moral e política e uma crise de legitimidade no centro imperial como o movimento em apoio ao Vietnã fez?

O movimento em apoio à Palestina tem sido, eu acho, o desenvolvimento mais esperançoso no Ocidente no período recente. Podemos estabelecer um paralelo entre isso e o movimento contra a Guerra do Vietnã na década de 1960, do qual você foi um protagonista? Você acha que o apoio quase unânime dos governos ocidentais ao genocídio em Gaza de alguma forma sairá pela culatra, provocando uma crise moral e política e uma crise de legitimidade no centro imperial como o movimento em apoio ao Vietnã fez?

Tariq Ali

Há várias coisas a serem ditas sobre isso. Primeiro, não é como o movimento vietnamita e o movimento de solidariedade com o Vietnã, porque esse movimento, para a maioria de nós que participamos dele, tinha um conteúdo social muito claro. Não era apenas para a libertação nacional. Por mais falho que fosse, era liderado por um partido comunista cujo líder central era um sujeito do Comintern, Ho Chi Minh. Isso teve um grande impacto em todos os lugares, especialmente onde havia partidos comunistas de massa. Isso criou tensões dentro desses partidos, com as lideranças dizendo: "Apoiamos os vietnamitas, mas não digam isso muito alto". Foi [um conflito de] "paz no Vietnã" versus "vitória para os vietnamitas". Isso nos permitiu dividir esses partidos, em particular suas alas jovens, por toda a Europa.

Aqui, na Grã-Bretanha, a extrema esquerda combinada era maior do que a ala jovem do Partido Comunista. A extrema esquerda e sua periferia hegemonizaram a juventude muito rapidamente. É por isso que organizamos ocupações universitárias. O SWP [na época, chamado de Socialistas Internacionais] e o jovem Grupo Marxista Internacional desempenharam um grande papel nisso, mesmo que os números fossem pequenos. Isso variou de país para país, mas aconteceu no auge do século XX. A maneira como os vietnamitas clamavam pelo internacionalismo foi absolutamente crucial.

Então, a maneira como a luta vietnamita foi conduzida, a maneira como os vietnamitas clamavam pelo internacionalismo, foi absolutamente crucial. Lembro-me de uma vez no Vietnã do Norte, quando estava com o primeiro-ministro norte-vietnamita, Pham Van Dong, eu disse, na frente de muitas pessoas, "Camarada, hora das Brigadas Internacionais". Ele me chamou de lado e disse: "Olha, vou lhe dizer qual é o problema. Esta não é a Espanha, que faz parte da Europa. Este é um país muito distante. Então, apenas transportar vocês para propaganda política nos custaria muito dinheiro, e não temos tanto. Então, temos que garantir que vocês estejam protegidos. Porque esta não é uma guerra travada com rifles, os americanos estão nos bombardeando o tempo todo, eles vão matar alguns de vocês."

Eu disse: "E daí? Seu povo está morrendo." Ele disse, usando estas palavras: "Não, não é uma boa ideia. Uma ideia melhor é voltar e construir movimentos de massa em solidariedade conosco. Muito mais útil do que um pequeno show." Eu disse: "O cônsul-geral britânico em Hanói, que lutou na Segunda Guerra Mundial, me disse durante o chá há três dias que quando ouviu os bombardeiros chegando, sentiu vontade de pegar uma arma e ir para o teto e atirar neles." Pham Van Dong disse: "Bem, por que ele não faz isso? Não vamos impedi-lo." Ele quis dizer: vocês são doces e legais e nós apreciamos isso. Ele me abraçou muito calorosamente e disse que não seria útil porque os tempos mudaram.

A outra razão que Pham Van Dong me deu para não ter voluntários foi que eles estavam em um caminho muito complicado entre os russos e os chineses: "Se fizermos um grande apelo, sabemos que milhares de pessoas virão da Europa e de outros lugares, mas seremos convocados pelo presidente Mao e pela liderança russa, dizendo: 'O que você quer? Por que deixar essas pessoas loucas entrarem? Você está dizendo que não estamos dando armas o suficiente para vocês?’ Então, não entramos nisso. É apenas mais fácil.” Então, a FI decidiu que construir o movimento de solidariedade com o Vietnã era uma prioridade central — uma das melhores coisas que eles já fizeram. Ao contrário dos palestinos, os vietnamitas tinham um estado no Norte e enorme apoio material dos soviéticos e chineses.

A outra grande diferença era que, diferentemente dos palestinos, os vietnamitas tinham um estado no Norte e enorme apoio material dos soviéticos e chineses. Eles conquistaram cada vez mais vitórias no terreno. Participei de uma palestra em Hanói com seus principais comandantes militares, onde alguns de nós fomos autorizados a entrar. Um oficial de alta patente explicou como eles iriam esmagar os americanos.

Eu estava cético. Eu disse: "Esmagar os americanos? Olha o que está acontecendo." O coronel disse: "Temos um plano, uma combinação de ataques de guerrilha e ataques repentinos em massa para tomá-los." Ele basicamente descreveu a Ofensiva do Tet. Então, eles estavam muito convencidos, e nós dissemos: "Podemos realmente vencer esta. Isso seria um grande golpe contra os americanos." E eles venceram. Essa era a atmosfera.

A Palestina também é diferente no sentido de que para a geração mais jovem — não para as anteriores — a guerra em Gaza foi um grande choque. No começo, os bons elementos reagiram a isso como reagiriam ao Black Lives Matter: ocupar os parques e tudo mais. Mas gradualmente isso se aprofundou, e algo aconteceu que não aconteceu com todos esses movimentos do estilo Black Lives Matter: eles começaram a ler e a fazer perguntas. Um elemento muito importante nos Estados Unidos foi a entrada de jovens judeus no movimento. Eu não conseguia acreditar nos meus olhos quando vi que os jovens judeus antisionistas ocuparam a Grand Central Station e disseram ao resto do movimento: "Este é o nosso negócio, deixe-nos fazer isso sozinhos". Na Grã-Bretanha, também, eles tinham suas próprias faixas, mas nunca fizeram coisas independentes como os jovens judeus americanos fizeram.

Isso abalou os israelenses e o AIPAC [American Israel Public Affairs Committee], mas não tocou os políticos, é claro. Meu próprio sentimento é que isso criou uma nova consciência. Se não podemos descrevê-lo como totalmente anti-imperialista, não está tão longe disso. As pessoas percebem que é isso que os israelenses estão fazendo com nosso dinheiro, com nossas bombas, em alguns casos com nossos soldados, e é inaceitável.

Estou otimista de que algo sairá disso. Há admiração pelos palestinos que revidam e total desgosto pelos soldados que eles veem murmurando obscenidades no estilo nazista contra os palestinos, como "Nossas crianças precisam de proteção porque não são como crianças árabes". Esses tipos de cânticos de "Matem os árabes" são repetidos por seus apoiadores aqui. Isso criou um forte sentimento de que todas as instituições criadas pelos Estados Unidos após a Segunda Guerra Mundial são inúteis a menos que os americanos as apoiem, começando com as grandes chamadas Nações Unidas e todos os tribunais internacionais que eles tentaram sabotar. Um elemento muito importante nos Estados Unidos foi a entrada de jovens judeus no movimento de solidariedade à Palestina.

O efeito nas novas gerações é muito positivo. Ironicamente, o estado americano logo perceberá isso. Qualquer outro país pode agora dizer: "Quem é você para nos dizer alguma coisa? Podemos ir e fazer nossas próprias atrocidades como os israelenses fizeram. Por que deveríamos ouvir você?” Na verdade, toda a estrutura das relações internacionais foi abalada por essa guerra em particular. Os israelenses, apoiados pelo Ocidente, travaram um genocídio contra o povo palestino e suas consequências permanecerão conosco por muito tempo. Esta é uma memória que não irá embora — e onde quer que os EUA façam isso agora, as pessoas reagirão dizendo: “Vá embora! Não faça isso. Não acreditamos em você.” E acho que também teve um efeito, quer as pessoas gostem ou não, nas percepções da Ucrânia: “Você diz que a Ucrânia é sagrada, você a defende. Não podemos fazer isso, não podemos fazer aquilo, porque pode ofendê-los. E na Palestina, você apenas assiste livremente.”

Intervenções imperialistas no Oriente Médio

Stathis Kouvelakis

Uma última pergunta sobre os últimos acontecimentos no Oriente Médio. Qual é sua atitude quando ditadores são derrubados no Iraque, Líbia e agora na Síria?

Tariq Ali

Não há motivo para comemoração quando esses atos são realizados por imperialismos ocidentais sob a liderança dos Estados Unidos. Quando eles são derrubados por seu próprio povo, eu comemoro. O Ocidente remove as pessoas de quem não gosta em um momento específico. Saddam [Hussein] do Iraque foi um herói quando agiu pelos EUA e começou uma guerra com o Irã. Ele se tornou um "Hitler" apenas quando invadiu o Kuwait, imaginando que tinha sinal verde dos EUA. Então, depois do 11 de setembro, eles acabaram com ele e um milhão de outros iraquianos. Cinco milhões de órfãos. Então eles lincharam Saddam. Motivo para comemoração? Eu escrevi contra ele e produzi um documentário zombando dele quando ele estava vivo.

Na Líbia, a OTAN matou mais de 30.000 líbios para forçar a mudança de regime e linchar Muammar Gaddafi. "Nós viemos, nós vimos, ele morreu" foi a celebração de Hillary Clinton. Políticos franceses e britânicos tiraram dinheiro de Gaddafi. A [London School of Economics implorou por uma grande doação e seus professores escreveram o doutorado do jovem Gaddafi para ele. Lord Anthony Giddens [o teórico da "Terceira Via" de Tony Blair] comparou a Líbia a uma "Noruega do Norte da África".

As mesmas pessoas apoiaram o ataque da OTAN. Eu o critiquei severamente por muitos anos. Eu não comemorei sua morte. O que há para comemorar nas palhaçadas do imperialismo ocidental? O mesmo para a Síria. O Iraque ainda não se recuperou. A Líbia está em ruínas, governada por jihadistas rivais. A Síria já foi dividida. O enorme triunfo do Ocidente ainda está se desenrolando.

Eles não têm mais vergonha de exibir seus padrões duplos como observamos com o genocídio israelense na Palestina, mas os idiotas úteis da OTAN em Londres, Paris, Roma, Berlim, adornos da mídia burguesa e seus apoiadores na esquerda quase inexistente, ainda fingem que avanços estão sendo feitos. Em uma de suas observações sobre teatro, Bertolt Brecht enfatizou que estava interessado nos "novos dias ruins, não nos velhos bons". Não há mais bons dias restantes. Séculos antes dele, Baruch Spinoza — que acabou de ter sua sentença de expulsão anulada pela Sinagoga em Amsterdã — ofereceu seu próprio conselho: "Nem rir nem chorar, mas entender". Os liberais da OTAN devem refletir sobre isso.

Colaboradores

Tariq Ali é editor da New Left Review.

Stathis Kouvelakis é um pesquisador independente em teoria política. Membro do comitê central do Syriza de 2012 a 2015, ele foi candidato pela MeRA25-Aliança pela Ruptura nas eleições gerais gregas de maio de 2023.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário