Tradução / A "luta por reconhecimento" está rapidamente se tornando a forma paradigmática de conflito político no final do século XX. Demandas por "reconhecimento da diferença" dão combustível às lutas de grupos mobilizados sob as bandeiras da nacionalidade, etnicidade, "raça", gênero e sexualidade. Nestes conflitos "pós-socialistas", a identidade de grupo suplanta o interesse de classe como o meio principal da mobilização política. A dominação cultural suplanta a exploração como a injustiça fundamental. E o reconhecimento cultural toma o lugar da redistribuição socioeconômica como remédio para a injustiça e objetivo da luta política.

Claro que esta não é toda a história. Lutas pelo reconhecimento ocorrem num mundo de exacerbada desigualdade material - desigualdades de renda e propriedade; de acesso a trabalho remunerado, educação, saúde e lazer; e também, mais cruamente, de ingestão calórica e exposição à contaminação ambiental; portanto, de expectativa de vida e de taxas de morbidade e mortalidade. A desigualdade material está em alta na maioria dos países do mundo - nos EUA e na China, na Suécia e na Índia, na Rússia e no Brasil. Ela também aumenta globalmente, de modo mais dramático, do outro lado da linha que divide norte e sul. Como, então, devemos ver o eclipse de um imaginário socialista centrado em termos como “interesse”, “exploração” e “redistribuição”? E o que devemos fazer com a emergência de um novo imaginário político centrado nas noções de “identidade”, “diferença”, “dominação cultural” e “reconhecimento”? Essa virada representa um lapso de “falsa consciência”? Ou seria mais um meio de compensar a cegueira cultural de um paradigma marxista posto em descrédito pelo colapso do comunismo soviético?

Nenhuma das duas posições é adequada, a meu ver. Ambas são demasiado abrangentes e sem nuanças. Ao invés de simplesmente endossar ou rejeitar o que é simplório na política da identidade, devíamos nos dar conta de que temos pela frente uma nova tarefa intelectual e prática: a de desenvolver uma teoria crítica do reconhecimento, que identifique e assuma a defesa somente daquelas versões da política cultural da diferença que possam ser combinadas coerentemente com a política social da igualdade.

Ao formular esse projeto, assumo que a justiça hoje exige tanto redistribuição como reconhecimento. E proponho examinar a relação entre eles. Isso significa, em parte, pensar em como conceituar reconhecimento cultural e igualdade social de forma a que sustentem um ao outro, ao invés de se aniquilarem (pois há muitas concepções concorrentes de ambos!) Significa também teorizar a respeito dos meios pelos quais a privação econômica e o desrespeito cultural se entrelaçam e sustentam simultaneamente. Exige também, portanto, esclarecer os dilemas políticos que surgem quando tentamos combater as duas injustiças ao mesmo tempo.

Meu objetivo maior é ligar duas problemáticas políticas atualmente dissociadas; pois é somente integrando reconhecimento e redistribuição que chegaremos a um quadro conceitual adequado às demandas de nossa era. That, however, is far too much to take on here. In what follows, I shall consider only one aspect of the problem. Under what circumstances can a politics of recognition help support a politics of redistribution? And when is it more likely to undermine it? Which of the many varieties of identity politics best synergize with struggles for social equality? And which tend to interfere with the latter?

In addressing these questions, I shall focus on axes of injustice that are simultaneously cultural and socioeconomic, paradigmatically gender and ‘race’. (I shall not say much, in contrast, about ethnicity or nationality.footnote1) And I must enter one crucial preliminary caveat: in proposing to assess recognition claims from the standpoint of social equality, I assume that varieties of recognition politics that fail to respect human rights are unacceptable even if they promote social equality.footnote2

Finally, a word about method: in what follows, I shall propose a set of analytical distinctions, for example, cultural injustices versus economic injustices, recognition versus redistribution. In the real world, of course, culture and political economy are always imbricated with one another; and virtually every struggle against injustice, when properly understood, implies demands for both redistribution and recognition. Nevertheless, for heuristic purposes, analytical distinctions are indispensable. Only by abstracting from the complexities of the real world can we devise a conceptual schema that can illuminate it. Thus, by distinguishing redistribution and recognition analytically, and by exposing their distinctive logics, I aim to clarify—and begin to resolve—some of the central political dilemmas of our age.

My discussion proceeds in four parts. In section one, I conceptualize redistribution and recognition as two analytically distinct paradigms of justice, and I formulate ‘the redistribution–recognition dilemma’. In section two, I distinguish three ideal-typical modes of social collectivity in order to identify those vulnerable to the dilemma. In section three, I distinguish between ‘affirmative’ and ‘transformative’ remedies for injustice, and I examine their respective logics of collectivity. Lastly, I use these distinctions, in section four, to propose a political strategy for integrating recognition claims with redistribution claims with a minimum of mutual interference.

I. The Redistribution-Recognition Dilemma

Let me begin by noting some complexities of contemporary ‘postsocialist’ political life. With the decentring of class, diverse social movements are mobilized around cross-cutting axes of difference. Contesting a range of injustices, their claims overlap and at times conflict. Demands for cultural change intermingle with demands for economic change, both within and among social movements. Increasingly, however, identity-based claims tend to predominate, as prospects for redistribution appear to recede. The result is a complex political field with little programmatic coherence.

Para ajudar a esclarecer esta situação e as perspectivas políticas que ela apresenta, proponho distinguir analiticamente duas maneiras muito genéricas de compreender a injustiça. A primeira delas é a injustiça econômica, que se radica na estrutura econômico-política da sociedade. Seus exemplos incluem a exploração (ser expropriado do fruto do próprio trabalho em benefício de outros); a marginalização econômica (ser obrigado a um trabalho indesejável e mal pago, como também não ter acesso a trabalho remunerado); e a privação (não ter acesso a um padrão de vida material adequado).

Teóricos igualitários empreenderam grande esforço para conceituar a natureza dessas injustiças socioeconômicas. Suas concepções incluem a teoria de Marx sobre a exploração capitalista; a concepção de justiça de Rawls, como justiça na seleção dos princípios que regem a distribuição dos “bens primários”; a visão de Amartya Sen, de que justiça implica “capacidades de função” iguais; e a de Ronald Dworkin, de que justiça implica “igualdade de recursos”. Para meus propósitos neste trabalho, porém, não precisamos nos comprometer com nenhuma visão teórica em particular. Precisamos apenas subscrever uma compreensão geral e rudimentar da injustiça socioeconômica informada por um compromisso com o igualitarismo.

A segunda maneira de compreender a injustiça é cultural ou simbólica. Aqui a injustiça se radica nos padrões sociais de representação, interpretação e comunicação. Seus exemplos incluem a dominação cultural (ser submetido a padrões de interpretação e comunicação associados a outra cultura, alheios e/ou hostis à sua própria); o ocultamento (tornar-se invisível por efeito das práticas comunicativas, interpretativas e representacionais autorizadas da própria cultura); e o desrespeito (ser difamado ou desqualificado rotineiramente nas representações culturais públicas estereotipadas e/ou nas interações da vida cotidiana).

Some political theorists have recently sought to conceptualize the nature of these cultural or symbolic injustices. Charles Taylor, for example, has drawn on Hegelian notions to argue that:

Nonrecognition or misrecognition. . .can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, reduced mode of being. Beyond simple lack of respect, it can inflict a grievous wound, saddling people with crippling self-hatred. Due recognition is not just a courtesy but a vital human need.footnote4

Likewise, Axel Honneth has argued that:

we owe our integrity... to the receipt of approval or recognition from other persons. [Negative concepts such as ‘insult’ or ‘degradation’] are related to forms of disrespect, to the denial of recognition. [They] are used to characterize a form of behaviour that does not represent an injustice solely because it constrains the subjects in their freedom for action or does them harm. Rather, such behaviour is injurious because it impairs these persons in their positive understanding of self—an understanding acquired by intersubjective means.[5]

Similar conceptions inform the work of many other critical theorists who do not use the term ‘recognition.’footnote6 Once again, however, it is not necessary here to settle on a particular theoretical account. We need only subscribe to a general and rough understanding of cultural injustice, as distinct from socioeconomic injustice.

Despite the differences between them, both socioeconomic injustice and cultural injustice are pervasive in contemporary societies. Both are rooted in processes and practices that systematically disadvantage some groups of people vis-à-vis others. Both, consequently, should be remedied.footnote7

Of course, this distinction between economic injustice and cultural injustice is analytical. In practice, the two are intertwined. Even the most material economic institutions have a constitutive, irreducible cultural dimension; they are shot through with significations and norms. Conversely, even the most discursive cultural practices have a constitutive, irreducible political-economic dimension; they are underpinned by material supports. Thus, far from occupying two airtight separate spheres, economic injustice and cultural injustice are usually interimbricated so as to reinforce one another dialectically. Cultural norms that are unfairly biased against some are institutionalized in the state and the economy; meanwhile, economic disadvantage impedes equal participation in the making of culture, in public spheres and in everyday life. The result is often a vicious circle of cultural and economic subordination.[8]

Insistirei em distinguir analiticamente injustiça econômica e injustiça cultural, em que pese seu mútuo entrelaçamento. O remédio para a injustiça econômica é alguma espécie de reestruturação político-econômica. Pode envolver redistribuição de renda, reorganização da divisão do trabalho, controles democráticos do investimento ou a transformação de outras estruturas econômicas básicas. Embora esses vários remédios difiram significativamente entre si, doravante vou me referir a todo esse grupo pelo termo genérico “redistribuição”. O remédio para a injustiça cultural, em contraste, é alguma espécie de mudança cultural ou simbólica. Pode envolver a revalorização das identidades desrespeitadas e dos produtos culturais dos grupos difamados. Pode envolver, também, o reconhecimento e a valorização positiva da diversidade cultural. Mais radicalmente ainda, pode envolver uma transformação abrangente dos padrões sociais de representação, interpretação e comunicação, de modo a transformar o sentido do eu de todas as pessoas. Embora esses remédios difiram significativamente entre si, doravante vou me referir a todo esse grupo pelo termo genérico “reconhecimento”.

Once again, this distinction between redistributive remedies and recognition remedies is analytical. Redistributive remedies generally presuppose an underlying conception of recognition. For example, some proponents of egalitarian socioeconomic redistribution ground their claims on the ‘equal moral worth of persons’; thus, they treat economic redistribution as an expression of recognition.footnote11 Conversely, recognition remedies sometimes presuppose an underlying conception of redistribution. For example, some proponents of multicultural recognition ground their claims on the imperative of a just distribution of the ‘primary good’ of an ‘intact cultural structure’; they therefore treat cultural recognition as a species of redistribution.footnote12 Such conceptual entwinements notwith-standing, I shall leave to one side questions such as, do redistribution and recognition constitute two distinct, irreducible, sui generis concepts of justice, or alternatively, can either one of them be reduced to the other?footnote13 Rather, I shall assume that however we account for it metatheoretically, it will be useful to maintain a working, first-order distinction between socioeconomic injustices and their remedies, on the one hand, and cultural injustices and their remedies, on the other.footnote14

Postas estas distinções, posso passar agora à questão seguinte: qual é a relação entre lutas por reconhecimento, voltadas para remediar a injustiça cultural, e lutas por redistribuição, voltadas para compensar a injustiça econômica? E que espécie de interferências mútuas podem brotar quando os dois tipos de reivindicação são feitos simultaneamente?

Existem boas razões para se preocupar com essas interferências mútuas. Lutas de reconhecimento assumem com freqüência a forma de chamar a atenção para a presumida especificidade de algum grupo – ou mesmo de criá-la performativamente – e, portanto, afirmar seu valor. Desse modo, elas tendem a promover a diferenciação do grupo. Lutas de redistribuição, em contraste, buscam com freqüência abolir os arranjos econômicos que embasam a especificidade do grupo (um exemplo seriam as demandas feministas para abolir a divisão do trabalho segundo o gênero). Desse modo, elas tendem a promover a desdiferenciação do grupo. O resultado é que a política do reconhecimento e a política da redistribuição parecem ter com freqüência objetivos mutuamente contraditórios. Enquanto a primeira tende a promover a diferenciação do grupo, a segunda tende a desestabilizá-la. Desse modo, os dois tipos de luta estão em tensão; um pode interferir no outro, ou mesmo agir contra o outro.

Eis, então, um difícil dilema. Doravante vou chamá-lo dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento. Pessoas sujeitas à injustiça cultural e à injustiça econômica necessitam de reconhecimento e redistribuição. Necessitam de ambos para reivindicar e negar sua especificidade. Como isso é possível?

Before taking up this question, let us consider precisely who faces the recognition–redistribution dilemma.

II. Exploited Classes, Despised Sexualities, and Bivalent Collectivities

Imagine a conceptual spectrum of different kinds of social collectivities. At one extreme are modes of collectivity that fit the redistribution model of justice. At the other extreme are modes of collectivity that fit the recognition model. In between are cases that prove difficult because they fit both models of justice simultaneously.

Consider, first, the redistribution end of the spectrum. At this end let us posit an ideal-typical mode of collectivity whose existence is rooted wholly in the political economy. It will be differentiated as a collectivity, in other words, by virtue of the economic structure, as opposed to the cultural order, of society. Thus any structural injustices its members suffer will be traceable ultimately to the political economy. The root of the injustice, as well as its core, will be socioeconomic maldistribution, while any attendant cultural injustices will derive ultimately from that economic root. At bottom, therefore, the remedy required to redress the injustice will be political-economic redistribution, as opposed to cultural recognition.

In the real world, to be sure, political economy and culture are mutually intertwined, as are injustices of distribution and recognition. Thus we may doubt whether there exist any pure collectivities of this sort. For heuristic purposes, however, it is useful to examine their properties. To do so, let us consider a familiar example that can be interpreted as approximating the ideal type: the Marxian conception of the exploited class, understood in an orthodox and theoretical way.footnote15 And let us bracket the question of whether this view of class fits the actual historical collectivities that have struggled for justice in the real world in the name of the working class.footnote16

In the conception assumed here, class is a mode of social differentiation that is rooted in the political-economic structure of society. A class only exists as a collectivity by virtue of its position in that structure and of its relation to other classes. Thus, the Marxian working class is the body of persons in a capitalist society who must sell their labour-power under arrangements that authorize the capitalist class to appropriate surplus productivity for its private benefit. The injustice of these arrangements, moreover, is quintessentially a matter of distribution. In the capitalist scheme of social reproduction, the proletariat receives an unjustly large share of the burdens and an unjustly small share of the rewards. To be sure, its members also suffer serious cultural injustices, the ‘hidden (and not so hidden) injuries of class’. But far from being rooted directly in an autonomously unjust cultural structure, these derive from the political economy, as ideologies of class inferiority proliferate to justify exploitation.[17] The remedy for the injustice, consequently, is redistribution, not recognition. Overcoming class exploitation requires restructuring the political economy so as to alter the class distribution of social burdens and social benefits. In the Marxian conception, such restructuring takes the radical form of abolishing the class structure as such. The task of the proletariat, therefore, is not simply to cut itself a better deal, but ‘to abolish itself as a class’. The last thing it needs is recognition of its difference. On the contrary, the only way to remedy the injustice is to put the proletariat out of business as a group.

Now consider the other end of the conceptual spectrum. At this end we may posit an ideal-typical mode of collectivity that fits the recognition model of justice. A collectivity of this type is rooted wholly in culture, as opposed to in political economy. It only exists as a collectivity by virtue of the reigning social patterns of interpretation and evaluation, not by virtue of the division of labour. Thus, any structural injustices its members suffer will be traceable ultimately to the cultural-valuational structure. The root of the injustice, as well as its core, will be cultural misrecognition, while any attendant economic injustices will derive ultimately from that cultural root. At bottom, therefore, the remedy required to redress the injustice will be cultural recognition, as opposed to political-economic redistribution.

Once again, we may doubt whether there exist any pure collectivities of this sort, but it is useful to examine their properties for heuristic purposes. An example that can be interpreted as approximating the ideal type is the conception of a despised sexuality, understood in a specific stylized and theoretical way.footnote18 Let us consider this conception, while leaving aside the question of whether this view of sexuality fits the actual historical homosexual collectivities that are struggling for justice in the real world.

Sexuality in this conception is a mode of social differentiation whose roots do not lie in the political economy, as homosexuals are distributed throughout the entire class structure of capitalist society, occupy no distinctive position in the division of labour, and do not constitute an exploited class. Rather, their mode of collectivity is that of a despised sexuality, rooted in the cultural-valuational structure of society. From this perspective, the injustice they suffer is quintessentially a matter of recognition. Gays and lesbians suffer from heterosexism: the authoritative construction of norms that privilege heterosexuality. Along with this goes homophobia: the cultural devaluation of homosexuality. Their sexuality thus disparaged, homosexuals are subject to shaming, harassment, discrimination, and violence, while being denied legal rights and equal protections—all fundamentally denials of recognition. To be sure, gays and lesbians also suffer serious economic injustices; they can be summarily dismissed from work and are denied family-based social-welfare benefits. But far from being rooted directly in the economic structure, these derive instead from an unjust cultural-valuational structure.footnote19 The remedy for the injustice, consequently, is recognition, not redistribution. Overcoming homophobia and heterosexism requires changing the cultural valuations (as well as their legal and practical expressions) that privilege heterosexuality, deny equal respect to gays and lesbians, and refuse to recognize homosexuality as a legitimate way of being sexual. It is to revalue a despised sexuality, to accord positive recognition to gay and lesbian sexual specificity.

As coisas são bem claras nas duas extremidades de nosso espectro conceitual. Quando lidamos com coletividades que se aproximam do tipo ideal da classe trabalhadora explorada, encaramos injustiças distributivas que precisam de remédios redistributivos. Quando lidamos com coletividades que se aproximam do tipo ideal da sexualidade desprezada, em contraste, encaramos injustiças de discriminação negativa que precisam de remédios de reconhecimento. No primeiro caso, a lógica do remédio é acabar com esse negócio de grupo; no segundo caso, ao contrário, trata-se de valorizar o “sentido de grupo” do grupo, reconhecendo sua especificidade.

As coisas ficam mais turvas, porém, à medida que nos afastamos das extremidades. Quando consideramos coletividades localizadas na região intermediária do espectro conceitual, encontramos tipos híbridos que combinam características da classe explorada com características da sexualidade desprezada. Essas coletividades são “bivalentes”. São diferenciadas como coletividades tanto em virtude da estrutura econômico-política quanto da estrutura cultural-valorativa da sociedade. Oprimidas ou subordinadas, portanto, sofrem injustiças que remontam simultaneamente à economia política e à cultura. Coletividades bivalentes, em suma, podem sofrer da má distribuição socioeconômica e da desconsideração cultural de forma que nenhuma dessas injustiças seja um efeito indireto da outra, mas ambas primárias e co-originais. Nesse caso, nem os remédios de redistribuição nem os de reconhecimento, por si sós, são suficientes. Coletividades bivalentes necessitam dos dois.

Gênero e “raça” são paradigmas de coletividades bivalentes. Embora cada qual tenha peculiaridades não compartilhadas pela outra, ambas abarcam dimensões econômicas e dimensões cultural-valorativas. Gênero e “raça”, portanto, implicam tanto redistribuição quanto reconhecimento.

O gênero, por exemplo, tem dimensões econômico-políticas porque é um princípio estruturante básico da economia política. Por um lado, o gênero estrutura a divisão fundamental entre trabalho “produtivo” remunerado e trabalho “reprodutivo” e doméstico não-remunerado, atribuindo às mulheres a responsabilidade primordial por este último. Por outro lado, o gênero também estrutura a divisão interna ao trabalho remunerado entre as ocupações profissionais e manufatureiras de remuneração mais alta, em que predominam os homens, e ocupações de “colarinho rosa” e de serviços domésticos, de baixa remuneração, em que predominam as mulheres. O resultado é uma estrutura econômico-política que engendra modos de exploração, marginalização e privação especificamente marcados pelo gênero. Esta estrutura constitui o gênero como uma diferenciação econômico-política dotada de certas características da classe. Sob esse aspecto, a injustiça de gênero aparece como uma espécie de injustiça distributiva que clama por compensações redistributivas. De modo muito semelhante à classe, a injustiça de gênero exige a transformação da economia política para que se elimine a estruturação de gênero desta. Para eliminar a exploração, marginalização e privação especificamente marcadas pelo gênero é preciso abolir a divisão do trabalho segundo ele – a divisão de gênero entre trabalho remunerado e não-remunerado e dentro do trabalho remunerado. A lógica do remédio é semelhante à lógica relativa à classe: trata-se de acabar com esse negócio de gênero. Se o gênero não é nada mais do que uma diferenciação econômico-política, a justiça exige, em suma, que ele seja abolido.

Isso, no entanto, é apenas uma parte da história. Na verdade, o gênero não é somente uma diferenciação econômico-política, mas também uma diferenciação de valoração cultural. Como tal, ele também abarca elementos que se assemelham mais à sexualidade do que à classe, e isso permite enquadrá-lo na problemática do reconhecimento. Seguramente, uma característica central da injustiça de gênero é o androcentrismo: a construção autorizada de normas que privilegiam os traços associados à masculinidade. Em sua companhia está o sexismo cultural: a desqualificação generalizada das coisas codificadas como “femininas”, paradigmaticamente – mas não só –, as mulheres. Essa desvalorização se expressa numa variedade de danos sofridos pelas mulheres, incluindo a violência e a exploração sexual, a violência doméstica generalizada; as representações banalizantes, objetificadoras e humilhantes na mídia; o assédio e a desqualificação em todas as esferas da vida cotidiana; a sujeição às normas androcêntricas, que fazem com que as mulheres pareçam inferiores ou desviantes e que contribuem para mantê-las em desvantagem, mesmo na ausência de qualquer intenção de discriminar; a discriminação atitudinal; a exclusão ou marginalização das esferas públicas e centros de decisão; e a negação de direitos legais plenos e proteções igualitárias. Esses danos são injustiças de reconhecimento. São relativamente independentes da economia política e não são meramente “superestruturais”. Por isso, não podem ser remediados apenas pela redistribuição econômico-política, mas precisam de medidas independentes e adicionais de reconhecimento. O androcentrismo e sexismo predominantes exigem a mudança dos valores culturais (assim como de suas expressões legais e práticas) que privilegiam a masculinidade e negam respeito às mulheres. Exigem o descentramento das normas androcêntricas e a revalorização de um gênero desprezado. A lógica do remédio é semelhante à lógica relativa à sexualidade: conceder reconhecimento positivo a um grupo especificamente desvalorizado.

O gênero é, em suma, um modo bivalente de coletividade. Ele contém uma face de economia política, que o insere no âmbito da redistribuição. Mas também uma face cultural-valorativa, que simultaneamente o insere no âmbito do reconhecimento. Naturalmente, as duas faces não são claramente separadas uma da outra. Elas se entrelaçam para se reforçarem entre si dialeticamente porque as normas culturais sexistas e androcêntricas estão institucionalizadas no Estado e na economia e a desvantagem econômica das mulheres restringe a “voz” das mulheres, impedindo a participação igualitária na formação da cultura, nas esferas públicas e na vida cotidiana. O resultado é um círculo vicioso de subordinação cultural e econômica. Para compensar a injustiça de gênero, portanto, é preciso mudar a economia política e a cultura.

Mas o caráter bivalente do gênero é a fonte de um dilema. Uma vez que as mulheres sofrem, no mínimo, de dois tipos de injustiça analiticamente distintos, elas necessariamente precisam, no mínimo, de dois tipos de remédios analiticamente distintos: redistribuição e reconhecimento. Os dois remédios pendem para direções opostas, porém, e não é fácil persegui-las ao mesmo tempo. Enquanto a lógica da redistribuição é acabar com esse negócio de gênero, a lógica do reconhecimento é valorizar a especificidade de gênero. Eis, então, a versão feminista do dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento: como as feministas podem lutar ao mesmo tempo para abolir a diferenciação de gênero e para valorizar a especificidade de gênero?

Um dilema análogo aparece na luta contra o racismo. A “raça”, como o gênero, é um modo bivalente de coletividade. Por um lado, ela se assemelha à classe, sendo um princípio estrutural da economia política. Neste aspecto, a “raça” estrutura a divisão capitalista do trabalho. Ela estrutura a divisão dentro do trabalho remunerado, entre as ocupações de baixa remuneração, baixo status, enfadonhas, sujas e domésticas, mantidas desproporcionalmente pelas pessoas de cor, e as ocupações de remuneração mais elevada, de maior status, de “colarinho branco”, profissionais, técnicas e gerenciais, mantidas desproporcionalmente pelos “brancos”. A divisão racial contemporânea do trabalho remunerado faz parte do legado histórico do colonialismo e da escravidão, que elaborou categorizações raciais para justificar formas novas e brutais de apropriação e exploração, constituindo efetivamente os “negros” como uma casta econômico-política. Atualmente, além disso, a “raça” também estrutura o acesso ao mercado de trabalho formal, constituindo vastos segmentos da população de cor como subploretariado ou subclasse, degradado e “supérfluo” que não vale a pena ser explorado e é totalmente excluído do sistema produtivo. O resultado é uma estrutura econômico-política que engendra modos de exploração, marginalização e privação especificamente marcados pela “raça”. Essa estrutura constitui a raça como uma diferenciação econômico-política dotada de certas características de classe. Sob esse aspecto, a injustiça racial aparece como uma espécie de injustiça distributiva que clama por compensações redistributivas. De modo muito semelhante à classe, a injustiça racial exige a transformação da economia política para que se elimine a racialização desta. Para eliminar a exploração, marginalização e privação especificamente marcadas pela “raça” é preciso abolir a divisão racial do trabalho – a divisão racial entre trabalho explorável e supérfluuo e a divisão racial dentro do trabalho remunerado. A lógica do remédio é semelhante à lógica relativa à classe: trata-se de fazer com que a “raça” fique fora do negócio. Se a “raça” não é nada mais do que uma diferenciação econômico-política, a justiça exige, em suma, que ela seja abolida.

Entretanto, a raça, como o gênero, não é somente econômico-política. Ela também tem dimensões culturais-valorativas, que a inserem no universo do reconhecimento. Assim, a “raça” também abarca elementos mais parecidos com a sexualidade do que com a classe. Um aspecto central do racismo é o eurocentrismo: a construção autorizada de normas que privilegiam os traços associados com o “ser branco”. Em sua companhia está o racismo cultural: a desqualificação generalizada das coisas codificadas como “negras”, “pardas” e “amarelas”, paradigmaticamente – mas não só – as pessoas de cor. Esta depreciação se expressa numa variedade de danos sofridos pelas pessoas de cor, incluindo representações estereotipadas e humilhantes na mídia, como criminosos, brutais, primitivos, estúpidos etc; violência, assédio e difamação em todas as esferas da vida cotidiana; sujeição às normas eurocêntricas que fazem com que as pessoas de cor pareçam inferiores ou desviantes e que contribuem para mantê-las em desvantagem mesmo na ausência de qualquer intenção de discriminar; a discriminação atitudinal; a exclusão e/ou marginalização das esferas públicas e centros de decisão; e a negação de direitos legais plenos e proteções igualitárias. Como no caso do gênero, esses danos são injustiças de reconhecimento. Por isso, a lógica do remédio também é conceder reconhecimento positivo a um grupo especificamente desvalorizado.

A “raça” também é, portanto, um modo bivalente de coletividade com uma face econômico- política e uma face cultural-valorativa. Suas duas faces se entrelaçam para se reforçarem uma à outra, dialeticamente, ainda mais porque as normas culturais racistas e eurocêntricas estão institucionalizadas no Estado e na economia, e a desvantagem econômica sofrida pelas pessoas de cor restringe sua “voz”. Para compensar a injustiça racial, portanto, é preciso mudar a economia política e a cultura. Mas, como ocorre com o gênero, o caráter bivalente da “raça” é a fonte de um dilema. Uma vez que as pessoas de cor sofrem, no mínimo, de dois tipos de injustiça analiticamente distintos, elas necessariamente precisam, no mínimo, de dois tipos de remédios analiticamente distintos: redistribuição e reconhecimento, que não são facilmente conciliáveis. Enquanto a lógica da redistribuição é acabar com esse negócio de “raça”, a lógica do reconhecimento é valorizar a especificidade do grupo. Eis, então, a versão anti-racista do dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento: como os anti-racistas podem lutar ao mesmo tempo para abolir a “raça” e para valorizar a especificidade cultural dos grupos racializados subordinados?

Gênero e “raça” são, em suma, modos dilemáticos de coletividade. Diferentemente da classe, que ocupa uma das extremidades do espectro conceitual, e da sexualidade, que ocupa a outra, gênero e “raça” são bivalentes, implicados ao mesmo tempo na política de redistribuição e na política do reconhecimento. Ambos, conseqüentemente, enfrentam o dilema da redistribuição- reconhecimento. As feministas devem buscar remédios que dissolvam a diferenciação de gênero, enquanto buscam também remédios culturais que valorizem a especificidade de uma coletividade desprezada. Os anti-racistas, da mesma maneira, devem buscar remédios econômico- políticos que dissolvam a diferenciação “racial”, enquanto buscam também remédios culturais que valorizem a especificidade de coletividades desprezadas. Como podem fazer as duas coisas ao mesmo tempo?

III. Affirmation or Transformation? Revisiting the Question of Remedy

Até aqui, apresentei o dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento de uma forma que parece completamente intratável. Assumi que os remédios redistributivos para a injustiça econômico- política sempre diferenciam os grupos sociais. Da mesma maneira, assumi que os remédios de reconhecimento para a injustiça cultural-valorativa sempre realçam a diferenciação do grupo social. Diante dessas posições, é difícil ver como feministas e anti-racistas podem buscar redistribuição e reconhecimento ao mesmo tempo.

Agora, porém, quero complicar essas posições. Nesta seção, vou examinar concepções alternativas de redistribuição, de um lado, e concepções alternativas de reconhecimento, de outro. Meu objetivo é distinguir duas grandes abordagens para corrigir a injustiça que atravessam o divisor da redistribuição-reconhecimento. Vou chamá-las de “afirmação” e “transformação”, respectivamente. Após apresentá-las genericamente, mostrarei como cada uma opera em relação à redistribuição e ao reconhecimento. Por fim, a partir dessa base, vou reformular o dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento para uma forma mais aberta a uma resolução.

Vou começar por uma breve distinção entre afirmação e transformação. Por remédios afirmativos para a injustiça, entendo os remédios voltados para corrigir efeitos desiguais de arranjos sociais sem abalar a estrutura subjacente que os engendra. Por remédios transformativos, em contraste, entendo os remédios voltados para corrigir efeitos desiguais precisamente por meio da remodelação da estrutura gerativa subjacente. O ponto crucial do contraste é efeitos terminais vs. processos que os produzem – e não mudança gradual vs. mudança apocalíptica.

Pode-se aplicar essa distinção, primeiramente, aos remédios para a injustiça cultural. Remédios afirmativos para tais injustiças são presentemente associados ao que vou chamar “multiculturalismo mainstream”. Essa espécie de multiculturalismo propõe compensar o desrespeito por meio da revalorização das identidades grupais injustamente desvalorizadas, enquanto deixa intactos os conteúdos dessas identidades e as diferenciações grupais subjacentes a elas. Remédios transformativos, em contraste, são presentemente associados à desconstrução. Eles compensariam o desrespeito por meio da transformação da estrutura cultural- valorativa subjacente. Desestabilizando as identidades e diferenciações grupais existentes, esses remédios não somente elevariam a autoestima dos membros de grupos presentemente desrespeitados; eles transformariam o sentido do eu de todos.

Para ilustrar a distinção, vamos considerar, mais uma vez, o caso da sexualidade desprezada. Remédios afirmativos para a homofobia e o heterossexismo são presentemente associados com a política de identidade gay, que visa a revalorizar a identidade gay e lésbica. Remédios transformativos, em contraste, são associados à política queer, que se propõe a desconstruir a dicotomia homo-hétero. A política de identidade gay trata a homossexualidade como uma positividade cultural, com seu próprio conteúdo substantivo, muito semelhante à etnicidade (ou à visão de senso comum desta). Assume-se que essa positividade subsiste em si e de si mesma, necessitando somente de reconhecimento adicional. A política queer, em contraste, trata a homossexualidade como um correlato construído e desvalorizado da heterossexualidade; ambas são reificações da ambigüidade sexual e são co-definidas somente uma em relação à outra. O objetivo transformativo não é consolidar uma identidade gay, mas desconstruir a dicotomia homo-hétero de modo a desestabilizar todas as identidades sexuais fixas. A questão não é dissolver toda a diferença sexual numa identidade humana única e universal; mas sim manter um campo sexual de diferenças múltiplas, não-binárias, fluidas, sempre em movimento.

As duas abordagens são de considerável interesse como remédios para a ausência de reconhecimento. Mas há uma diferença considerável entre elas. Enquanto a política de identidade gay tende a realçar a diferenciação de grupo sexual existente, a política queer tende a desestabilizá-la – no mínimo, ostensivamente e no longo prazo. A observação vale para os remédios de reconhecimento, de modo geral. Enquanto os remédios de reconhecimento afirmativos tendem a promover as diferenciações de grupo existentes, os remédios de reconhecimento transformativos tendem, no longo prazo, a desestabilizá-las, a fim de abrir espaço para futuros reagrupamentos. I shall return to this point shortly.

Distinções análogas valem para os remédios para a injustiça econômica. Os remédios afirmativos para essas injustiças estão associados historicamente ao Estado de bem-estar liberal. Eles buscam compensar a má distribuição terminal, enquanto deixam intacta a maior parte da estrutura econômico-política subjacente. Assim, eles aumentariam a parte de consumo dos grupos economicamente desprivilegiados, reestruturar o sistema de produção. Remédios transformativos, em contraste, são associados historicamente ao socialismo. Eles compensariam a distribuição injusta transformando a estrutura econômico-política existente. Reestruturando as relações de produção, esses remédios não somente alterariam a distribuição terminal das partes de consumo; mudariam também a divisão social do trabalho e, assim, as condições de existência de todos.

Para ilustrar a distinção, vamos considerar, mais uma vez, o caso da classe explorada. Remédios de redistribuição afirmativos para as injustiças de classe freqüentemente incluem transferências de renda de dois tipos distintos: programas de seguro social dividem parte dos custos de reprodução social dos empregados formais, os chamados setores primários da classe trabalhadora; programas de assistência pública oferecem auxílios “focalizados” ao “exército de reserva” de desempregados e subempregados. Longe de abolirem a divisão de classes per se, esses remédios afirmativos sustentam-na e moldam-na. Seu efeito geral é desviar a atenção da divisão de classes entre trabalhadores e capitalistas para a divisão entre as frações empregadas e desempregadas da classe trabalhadora. Programas de assistência pública “focalizam” os pobres não só por auxílio, mas por hostilidade. Tais remédios, com certeza, oferecem a ajuda material necessitada. Mas também criam diferenciações de grupo fortemente antagônicas.

A lógica aqui se aplica à redistribuição afirmativa em geral. Embora essa abordagem vise a compensar a injustiça econômica, ela deixa intactas as estruturas profundas que engendram a desvantagem de classe. Assim, é obrigada a fazer realocações superficiais constantemente. O resultado é marcar a classe mais desprivilegiada como inerentemente deficiente e insaciável, sempre necessitando mais e mais. Com o tempo essa classe pode mesmo aparecer como privilegiada, recebedora de tratamento especial e generosidade imerecida. Assim, uma abordagem voltada para compensar injustiças de distribuição pode acabar criando injustiças de reconhecimento.

Em certo sentido, esta abordagem é internamente contraditória. A redistribuição afirmativa, em geral, pressupõe uma concepção universalista de reconhecimento, a igualdade de valor moral das pessoas. Vamos chamar isso seu “compromisso formal de reconhecimento”. Entretanto, a prática da redistribuição afirmativa, reiterada ao longo do tempo, tende a pôr em movimento uma dinâmica secundária de reconhecimento estigmatizante, que contradiz seu compromisso formal com o universalismo. Essa dinâmica secundária, estigmatizante, pode ser entendida como o “efeito de reconhecimento prático” da redistribuição afirmativa. [35] It conflicts with its official recognition commitment.[36]

Vamos, agora, contrastar essa lógica com os remédios transformativos para as injustiças distributivas de classe. Remédios transformativos comumente combinam programas universalistas de bem-estar social, impostos elevados, políticas macroeconômicas voltadas para criar pleno emprego, um vasto setor público não-mercantil, propriedades públicas e/ou coletivas significativas, e decisões democráticas quanto às prioridades socioeconômicas básicas. Eles procuram garantir a todos o acesso ao emprego, enquanto tendem também a desvincular a parte básica de consumo e o emprego. Logo, sua tendência é dissolver a diferenciação de classe. Remédios transformativos reduzem a desigualdade social, porém sem criar classes estigmatizadas de pessoas vulneráveis vistas como beneficiárias de uma generosidade especial. Eles tendem, portanto, a promover reciprocidade e solidariedade nas relações de reconhecimento. Assim, uma abordagem voltada a compensar injustiças de distribuição pode ajudar também a compensar (algumas) injustiças de reconhecimento.

Essa abordagem é internamente consistente. Como a redistribuição afirmativa, a redistribuição transformativa em geral pressupõe uma concepção universalista de reconhecimento, a igualdade de valor moral das pessoas. Diferente da redistribuição afirmativa, contudo, sua prática tende a não dissolver essa concepção. Assim, as duas abordagens engendram diferentes lógicas de diferenciação de grupo. Enquanto os remédios afirmativos podem ter o efeito perverso de promover a diferenciação de classe, os remédios transformativos tendem a embaça-la. Além disso, as duas abordagens engendram diferentes dinâmicas subliminares de reconhecimento. A redistribuição afirmativa pode estigmatizar os desprivilegiados, acrescentando o insulto do menosprezo à injúria da privação. A redistribuição transformativa, em contraste, pode promover a solidariedade, ajudando a compensar algumas formas de não-reconhecimento.

O que devemos concluir, pois, desta discussão? Nesta seção, consideramos somente os casos típico-ideais “puros” nas duas extremidades do espectro conceitual. Contrastamos os efeitos divergentes dos remédios afirmativos e transformativos para as injustiças distributivas de classe, enraizadas economicamente, de um lado, e para as injustiças de reconhecimento da sexualidade, enraizadas culturalmente, de outro. Vimos que remédios afirmativos tendem, em geral, a promover a diferenciação de grupo, enquanto remédios transformativos tendem a desestabilizá-la ou embaçá-la. Vimos também que os remédios de redistribuição afirmativos podem engendrar um protesto de menosprezo, enquanto os remédios de redistribuição transformativos podem ajudar a compensar algumas formas de não-reconhecimento.

Tudo isso sugere um meio de reformular o dilema da redistribuição-reconhecimento. A pergunta que pode ficar é: no que diz respeito aos grupos submetidos aos dois tipos de injustiças, qual será combinação de remédios que funciona melhor para minimizar, senão para eliminar de vez, as interferências mútuas que surgem quando se busca redistribuição e reconhecimento ao mesmo tempo?

IV. Finessing the Dilemma: Revisiting Gender and "Race"

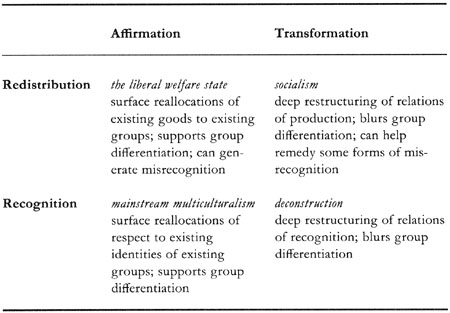

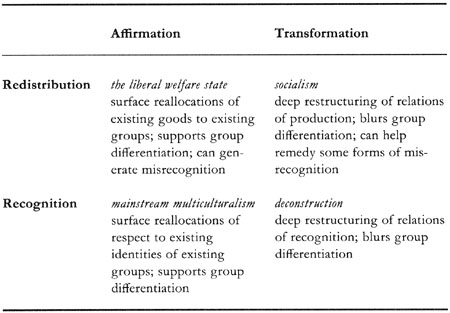

Imagine a four-celled matrix. The horizontal axis comprises the two general kinds of remedy we have just examined, namely, affirmation and transformation. The vertical axis comprises the two aspects of justice we have been considering, namely, redistribution and recognition. On this matrix we can locate the four political orientations just discussed. In the first cell, where redistribution and affirmation intersect, is the project of the liberal welfare state; centered on surface reallocations of distributive shares among existing groups, it tends to support group differentiation; it can also generate backlash misrecognition. In the second cell, where redistribution and transformation intersect, is the project of socialism; aimed at deep restructuring of the relations of production, it tends to blur group differentiation; it can also help redress some forms of misrecognition. In the third cell, where recognition and affirmation intersect, is the project of mainstream multiculturalism; focused on surface reallocations of respect among existing groups, it tends to support group differentiation. In the fourth cell, where recognition and transformation intersect, is the project of deconstruction; aimed at deep restructuring of the relations of recognition, it tends to destabilize group differentiations.

This matrix casts mainstream multiculturalism as the cultural analogue of the liberal welfare state, while casting deconstruction as the cultural analogue of socialism. It thereby it allows us to make some preliminary assessments of the mutual compatibility of various remedial strategies. We can gauge the extent to which pairs of remedies would work at cross-purposes with one another if they were pursued simultaneously. We can identify pairs that seem to land us squarely on the horns of the redistribution-recognition dilemma. We can also identify pairs that hold out the promise of enabling us to finesse it.

Prima facie at least, two pairs of remedies seem especially unpromising. The affirmative redistribution politics of the liberal welfare state seems at odds with the transformative recognition politics of deconstruction; whereas the first tends to promote group differentiation, the second tends rather to destabilize it. Similarly, the transformative redistribution politics of socialism seems at odds with the affirmative recognition politics of mainstream multiculturalism; whereas the first tends to undermine group differentiation, the second tends rather to promote it.

Conversely, two pairs of remedies seem comparatively promising. The affirmative redistribution politics of the liberal welfare state seems compatible with the affirmative recognition politics of mainstream multiculturalism; both tend to promote group differentiation. Similarly, the transformative redistribution politics of socialism seems compatible with the transformative recognition politics of deconstruction; both tend to undermine existing group differentiations.

To test these hypotheses, let us revisit gender and ‘race’. Recall that these are bivalent differentiations, axes of both economic and cultural injustice. Thus people subordinated by gender and/or ‘race’ need both redistribution and recognition. They are the paradigmatic subjects of the redistribution–recognition dilemma. What happens in their cases, then, when various pairs of injustice remedies are pursued simultaneously? Are there pairs of remedies that permit feminists and anti-racists to finesse, if not wholly to dispel, the redistribution–recognition dilemma?

Consider, first, the case of gender.footnote39 Recall that redressing gender injustice requires changing both political economy and culture, so as to undo the vicious circle of economic and cultural subordination. As we saw, the changes in question can take either of two forms, affirmation or transformation.footnote40 Let us consider, first, the prima facie promising case in which affirmative redistribution is combined with affirmative recognition. As the name suggests, affirmative redistribution to redress gender injustice in the economy includes affirmative action, the effort to assure women their fair share of existing jobs and educational places, while leaving unchanged the nature and number of those jobs and places. Affirmative recognition to redress gender injustice in the culture includes cultural feminism, the effort to assure women respect by revaluing femininity, while leaving unchanged the binary gender code that gives the latter its sense. Thus, the scenario in question combines the socioeconomic politics of liberal feminism with the cultural politics of cultural feminism. Does this combination really finesse the redistribution– recognition dilemma?

Despite its initial appearance of promise, this scenario is problematic. Affirmative redistribution fails to engage the deep level at which the political economy is gendered. Aimed primarily at combating attitudinal discrimination, it does not attack the gendered division of paid and unpaid labour, nor the gendered division of masculine and feminine occupations within paid labour. Leaving intact the deep structures that generate gender disadvantage, it must make surface reallocations again and again. The result is not only to underline gender differentiation. It is also to mark women as deficient and insatiable, as always needing more and more. In time women can even come to appear privileged, recipients of special treatment and undeserved largesse. Thus an approach aimed at redressing injustices of distribution can end up fuelling backlash injustices of recognition.

This problem is exacerbated when we add the affirmative recognition strategy of cultural feminism. That approach insistently calls attention to, if it does not performatively create, women’s putative cultural specificity or difference. In some contexts, such an approach can make progress toward decentring androcentric norms. In this context, however, it is more likely to have the effect of pouring oil onto the flames of resentment against affirmative action. Read through that lens, the cultural politics of affirming women’s difference appears as an affront to the liberal welfare state’s official commitment to the equal moral worth of persons.

The other route with a prima facie promise is that which combines transformative redistribution with transformative recognition. Transformative redistribution to redress gender injustice in the economy consists in some form of socialist feminism or feminist social democracy. And transformative recognition to redress gender injustice in the culture consists in feminist deconstruction aimed at dismantling androcentrism by destabilizing gender dichotomies. Thus the scenario in question combines the socioeconomic politics of socialist feminism with the cultural politics of deconstructive feminism. Does this combination really finesse the redistribution–recognition dilemma?

This scenario is far less problematic. The long-term goal of deconstructive feminism is a culture in which hierarchical gender dichotomies are replaced by networks of multiple intersecting differences that are demassified and shifting. This goal is consistent with transformative socialist-feminist redistribution. Deconstruction opposes the sort of sedimentation or congealing of gender difference that occurs in an unjustly gendered political economy. Its utopian image of a culture in which ever new constructions of identity and difference are freely elaborated and then swiftly deconstructed is only possible, after all, on the basis of rough social equality.

As a transitional strategy, moreover, this combination avoids fanning the flames of resentment.footnote41 If it has a drawback, it is rather that both deconstructive-feminist cultural politics and socialist-feminist economic politics are far removed from the immediate interests and identities of most women, as these are currently culturally constructed.

Analogous results arise for ‘race’, where the changes can again take either of two forms, affirmation or transformation.footnote42 In the first prima facie promising case, affirmative action is paired with affirmative recognition. Affirmative redistribution to redress racial injustice in the economy includes affirmative action, the effort to assure people of colour their fair share of existing jobs and educational places, while leaving unchanged the nature and number of those jobs and places. And affirmative recognition to redress racial injustice in the culture includes cultural nationalism, the effort to assure people of colour respect by revaluing ‘blackness’, while leaving unchanged the binary black–white code that gives the latter its sense. The scenario in question thus combines the socioeconomic politics of liberal anti-racism with the cultural politics of black nationalism or black power. Does this combination really finesse the redistribution–recognition dilemma?

Such a scenario is again problematic. As in the case of gender, here affirmative redistribution fails to engage the deep level at which the political economy is racialized. It does not attack the racialized division of exploitable and surplus labour, nor the racialized division of menial and non-menial occupations within paid labour. Leaving intact the deep structures that generate racial disadvantage, it must make surface reallocations again and again. The result is not only to underline racial differentiation. It is also to mark people of colour as deficient and insatiable, as always needing more and more. Thus they too can be cast as privileged recipients of special treatment. The problem is exacerbated when we add the affirmative recognition strategy of cultural nationalism. In some contexts, such an approach can make progress toward decentring Eurocentric norms, but in this context the cultural politics of affirming black difference equally appears as an affront to the liberal welfare state. Fuelling the resentment against affirmative action, it can elicit intense backlash misrecognition.

In the alternative route, transformative redistribution is combined with transformative recognition. Transformative redistribution to redress racial injustice in the economy consists in some form of anti-racist democratic socialism or anti-racist social democracy. And transformative recognition to redress racial injustice in the culture consists in anti-racist deconstruction aimed at dismantling Eurocentrism by destabilizing racial dichotomies. Thus, the scenario in question combines the socioeconomic politics of socialist anti-racism with the cultural politics of deconstructive anti-racism or critical ‘race’ theory. As with the analogous approach to gender, this scenario is far less problematic. The long-term goal of deconstructive anti-racism is a culture in which hierarchical racial dichotomies are replaced by demassified and shifting networks of multiple intersecting differences. This goal, once again, is consistent with transformative socialist redistribution. Even as a transitional strategy, this combination avoids fanning the flames of resentment.footnote43 Its principal drawback, again, is that both deconstructive–anti-racist cultural politics and socialist–anti-racist economic politics are far removed from the immediate interests and identities of most people of colour, as these are currently culturally constructed.[44]

What, then, should we conclude from this discussion? For both gender and ‘race’, the scenario that best finesses the redistribution–recognition dilemma is socialism in the economy plus deconstruction in the culture.footnote45 But for this scenario to be psychologically and politically feasible requires that people be weaned from their attachment to current cultural constructions of their interests and identities.[46]

V. Conclusion

The redistribution–recognition dilemma is real. There is no neat theoretical move by which it can be wholly dissolved or resolved. The best we can do is try to soften the dilemma by finding approaches that minimize conflicts between redistribution and recognition in cases where both must be pursued simultaneously.

I have argued here that socialist economics combined with deconstructive cultural politics works best to finesse the dilemma for the bivalent collectivities of gender and ‘race’—at least when they are considered separately. The next step would be to show that this combination also works for our larger sociocultural configuration. After all, gender and ‘race’ are not neatly cordoned off from one another. Nor are they neatly cordoned off from sexuality and class. Rather, all these axes of injustice intersect one another in ways that affect everyone’s interests and identities. No one is a member of only one such collectivity. And people who are subordinated along one axis of social division may well be dominant along another.[47]

The task then is to figure out how to finesse the redistribution– recognition dilemma when we situate the problem in this larger field of multiple, intersecting struggles against multiple, intersecting injustices. Although I cannot make the full argument task here, I will venture three reasons for expecting that the combination of socialism and deconstruction will again prove superior to the other alternatives.

First, the arguments pursued here for gender and ‘race’ hold for all bivalent collectivities. Thus, insofar as real-world collectivities mobilized under the banners of sexuality and class turn out to be more bivalent than the ideal-typical constructs posited above, they too should prefer socialism plus deconstruction. And that doubly transformative approach should become the orientation of choice for a broad range of disadvantaged groups.

Second, the redistribution–recognition dilemma does not only arise endogenously, as it were, within a single bivalent collectivity. It also arises exogenously, so to speak, across intersecting collectivities. Thus, anyone who is both gay and working-class will face a version of the dilemma, regardless of whether or not we interpret sexuality and class as bivalent. And anyone who is also female and black will encounter it in a multilayered and acute form. In general, then, as soon as we acknowledge that axes of injustice cut across one another, we must acknowledge cross-cutting forms of the redistribution–recognition dilemma. And these forms are, if anything, even more resistant to resolution by combinations of affirmative remedies than the forms we considered above. For affirmative remedies work additively and are often at cross purposes with one another. Thus, the intersection of class, ‘race’, gender, and sexuality intensifies the need for transformative solutions, making the combination of socialism and deconstruction more attractive still.

Third, that combination best promotes the task of coalition building. This task is especially pressing today, given the multiplication of social antagonisms, the fissuring of social movements, and the growing appeal of the Right in the United States. In this context, the project of transforming the deep structures of both political economy and culture appears to be the one over-arching programmatic orientation capable of doing justice to all current struggles against injustice. It alone does not assume a zero-sum game.

If that is right, then, we can begin to see how badly off track is the current us political scene. We are currently stuck in the vicious circles of mutually reinforcing cultural and economic subordination. Our best efforts to redress these injustices via the combination of the liberal welfare state plus mainstream multiculturalism are generating perverse effects. Only by looking to alternative conceptions of redistribution and recognition can we meet the requirements of justice for all.

*This article is a slightly revised version of a lecture presented at the University of Michigan in March 1995 at the Philosophy Department’s symposium on ‘Political Liberalism’. A longer version will appear in my forthcoming book, Justice Interruptus: Rethinking Key Concepts of a ‘Postsocialist’ Age. For generous research support, I thank the Bohen Foundation, the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna, the Humanities Research Institute of the University of California at Irvine, the Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research at Northwestern University, and the Dean of the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research. For helpful comments, I thank Robin Blackburn, Judith Butler, Angela Harris, Randall Kennedy, Ted Koditschek, Jane Mans-bridge, Mika Manty, Linda Nicholson, Eli Zaretsky, and the members of the ‘Feminism and the Discourses of Power’ work group at the Humanities Research Institute of the University of California, Irvine.

[1] This omission is dictated by reasons of space. I believe that the framework elaborated below can fruitfully address both ethnicity and nationality. Insofar as groups mobilized on these lines do not define themselves as sharing a situation of socioeconomic disadvantage and do not make redistributive claims, they can be understood as struggling primarily for recognition. National struggles are peculiar, however, in that the form of recognition they seek is political autonomy, whether in the form of a sovereign state of their own (e.g. the Palestinians) or in the form of more limited provincial sovereignty within a multinational state (e.g. the majority of Québecois). Struggles for ethnic recognition, in contrast, often seek rights of cultural expression within polyethnic nation-states. These distinctions are insightfully discussed in Will Kymlicka, ‘Three Forms of Group-Differentiated Citizenship in Canada’ (paper presented at the conference on ‘Democracy and Difference’, Yale University, 1993).

2My principal concern in this essay is the relation between the recognition of cultural difference and social equality. I am not directly concerned, therefore, with the relation between recognition of cultural difference and liberalism. However, I assume that no identity politics is acceptable that fails to respect fundamental human rights of the sort usually championed by left-wing liberals.

3Karl Marx, Capital, Volume 1; John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Cambridge, Mass. 1971 and subsequent papers; Amartya Sen, Commodities and Capabilities, North-Holland, 1985; and Ronald Dworkin, ‘What is Equality? Part 2: Equality of Resources’, Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 10, no. 4 (fall 1981). Although I here classify all these writers as theorists of distributive economic justice, it is also true that most of them have some resources for dealing with issues of cultural justice as well. Rawls, for example, treats ‘the social bases of self-respect’ as a primary good to be fairly distributed, while Sen treats a ‘sense of self’ as relevant to the capability to function. (I am indebted to Mika Manty for this point.) Nevertheless, as Iris Marion Young has suggested, the primary thrust of their thought leads in the direction of distributive economic justice. (See her Justice and the Politics of Difference, Princeton 1990.)

4Charles Taylor, Multiculturalism and ‘The Politics of Recognition’, Princeton 1992, p. 25.

5Axel Honneth, ‘Integrity and Disrespect: Principles of a Conception of Morality Based on the Theory of Recognition’, Political Theory, vol. 20, no. 2 (May 1992), pp. 188–9. See also his Kampf um Anerkennung, Frankfurt 1992; English translation forthcoming from The MIT Press under the title Struggle for Recognition. It is no accident that both of the major contemporary theorists of recognition, Honneth and Taylor, are Hegelians.

6See, for example, Patricia J. Williams, The Alchemy of Race and Rights, Cambridge, Mass. 1991; and Young, Justice and the Politics of Difference.

7Responding to an earlier draft of this paper, Mika Manty posed the question of whether/how a schema focused on classifying justice issues as either cultural or political-economic could accommodate ‘primary political concerns’ such as citizenship and political participation (‘Comments on Fraser’, unpublished typescript presented at the Michigan symposium on ‘Political Liberalism’). My inclination is to follow Jürgen Habermas in viewing such issues bifocally. From one perspective, political institutions (in state-regulated capitalist societies) belong with the economy as part of the ‘system’ that produces distributive socioeconomic injustices; in Rawlsian terms, they are part of ‘the basic structure’ of society. From another perspective, however, such institutions belong with ‘the lifeworld’ as part of the cultural structure that produces injustices of recognition; for example, the array of citizenship entitlements and participation rights conveys powerful implicit and explicit messages about the relative moral worth of various persons. ‘Primary political concerns’ could thus be treated as matters either of economic justice or cultural justice, depending on the context and perspective in play.

8For the interimbrication of culture and political economy, see my ‘What’s Critical About Critical Theory? The Case of Habermas and Gender’ in Nancy Fraser, Unruly Practices: Power, Discourse and Gender in Contemporary Social Theory, Oxford 1989; ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere’ in Fraser, Justice Interruptus; and Fraser, ‘Pragmatism, Feminism, and the Linguistic Turn’, in Benhabib, Butler, Cornell and Fraser, Feminist Contentions: A Philosophical Exchange, New York 1995. See also Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge 1977. For critiques of the cultural meanings implicit in the current us political economy of work and social welfare, see the last two chapters of Unruly Practices and the essays in Part 3 of justice Interruptus.

9In fact, these remedies stand in some tension with one another, a problem I shall explore in a subsequent section of this paper.

10These various cultural remedies stand in some tension with one another. It is one thing to accord recognition to existing identities that are currently undervalued; it is another to transform symbolic structures and thereby alter people’s identities. I shall explore the tensions among the various remedies in a subsequent section of the paper.

11For a good example of this approach, see Ronald Dworkin, ‘Liberalism’, in his A Matter of Principle, Cambridge, Mass. 1985.

12For a good example of this approach, see Will Kymlicka, Liberalism, Community and Culture, Oxford 1989. The case of Kymlicka suggests that the distinction between socioeconomic justice and cultural justice need not always map onto the distinction between distributive justice and relational or communicative justice.

13Axel Honneth’s Kampf um Anerkennung represents the most thorough and sophisticated attempt at such a reduction. Honneth argues that recognition is the fundamental concept of justice and can encompass distribution.

14Absent such a distinction, we foreclose the possibility of examining conflicts between them. We miss the chance to spot mutual interferences that could arise when redistribution claims and recognition claims are pursued simultaneously.

15In what follows, I conceive class in a highly stylized, orthodox, and theoretical way in order to sharpen the contrast to the other ideal-typical kinds of collectivity discussed below. Of course, this is hardly the only interpretation of the Marxian conception of class. In other contexts and for other purposes, I myself would prefer a less economistic interpretation, one that gives more weight to the cultural, historical and discursive dimensions of class emphasized by such writers as E. P. Thompson and Joan Wallach Scott. See Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, London 1963; and Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, New York 1988.

16It is doubtful that any collectivities mobilized in the real world today correspond to the notion of class presented below. Certainly, the history of social movements mobilized under the banner of class is more complex than this conception would suggest. Those movements have elaborated class not only as a structural category of political economy but also as a cultural-valuational category of identity—often in forms problematic for women and blacks. Thus, most varieties of socialism have asserted the dignity of labour and the worth of working people, mingling demands for redistribution with demands for recognition. Sometimes, moreover, having failed to abolish capitalism, class movements have adopted reformist strategies of seeking recognition of their ‘difference’ within the system in order to augment their power and support demands for what I below call ‘affirmative redistribution’. In general, then, historical class-based movements may be closer to what I below call ‘bivalent modes of collectivity’ than to the interpretation of class sketched here.

17This assumption does not require us to reject the view that distributive deficits are often (perhaps even always) accompanied by recognition deficits. But it does entail that the recognition deficits of class, in the sense elaborated here, derive from the political economy. Later, I shall consider other sorts of cases in which collectivities suffer from recognition deficits whose roots are not directly political-economic in this way.

18In what follows, I conceive sexuality in a highly stylized theoretical way in order to sharpen the contrast to the other ideal-typical kinds of collectivity discussed here. I treat sexual differentiation as rooted wholly in the cultural structure, as opposed to in the political economy. Of course, this is not the only interpretation of sexuality. Judith Butler (personal communication) has suggested that one might hold that sexuality is inextricable from gender, which, as I argue below, is as much a matter of the division of labour as of the cultural-valuational structure. In that case, sexuality itself might be viewed as a ‘bivalent’ collectivity, rooted simultaneously in culture and political economy. Then the economic harms encountered by homosexuals might appear economically rooted rather than culturally rooted, as they are in the account I offer here. While this bivalent analysis is certainly possible, to my mind it has serious drawbacks. Yoking gender and sexuality together too tightly, it covers over the important distinction between a group that occupies a distinct position in the division of labour (and that owes its existence in large part to this fact), on the one hand, and one that occupies no such distinct position, on the other hand. I discuss this distinction below.

19An example of an economic injustice rooted directly in the economic structure would be a division of labour that relegates homosexuals to a designated disadvantaged position and exploits them as homosexuals. To deny that this is the situation of homosexuals today is not to deny that they face economic injustices. But it is to trace these to another root. In general, I assume that recognition deficits are often (perhaps even always) accompanied by distribution deficits. But I nevertheless hold that the distribution deficits of sexuality, in the sense elaborated here, derive ultimately from the cultural structure. Later, I shall consider other sorts of cases in which collectivities suffer from recognition deficits whose roots are not (only) directly cultural in this sense. I can perhaps further clarify the point by invoking Oliver Cromwell Cox’s contrast between anti-Semitism and white supremacy. Cox suggested that for the anti-Semite, the very existence of the Jew is an abomination; hence the aim is not to exploit the Jew but to eliminate him/her as such, whether by expulsion, forced conversion, or extermination. For the white supremacist, in contrast, the ‘Negro’ is just fine—in his/her place: as an exploitable supply of cheap, menial labour power; here the preferred aim is exploitation, not elimination. (See Cox’s unjustly neglected masterwork, Caste, Class, and Race, New York 1970.) Contemporary homophobia appears in this respect to be more like anti-Semitism than white supremacy: it seeks to eliminate, not exploit, homosexuals. Thus, the economic disadvantages of homosexuality are derived effects of the more fundamental denial of cultural recognition. This makes it the mirror image of class, as just discussed, where the ‘hidden (and not so hidden) injuries’ of misrecognition are derived effects of the more fundamental injustice of exploitation. White supremacy, in contrast, as I shall suggest shortly, is ‘bivalent’, rooted simultaneously in political economy and culture, inflicting co-original and equally fundamental injustices of distribution and recognition. (On this last point, incidentally, I differ from Cox, who treats white supremacy as effectively reducible to class.)

20Gender disparagement can take many forms, of course, including conservative stereotypes that appear to celebrate, rather than demean, ‘femininity’.

21This helps explain why the history of women’s movements records a pattern of oscillation between integrationist equal-rights feminisms and ‘difference’-oriented ‘social’ and ‘cultural’ feminisms. It would be useful to specify the precise temporal logic that leads bivalent collectivities to shift their principal focus back and forth between redistribution and recognition. For a first attempt, see my ‘Rethinking Difference’ in Justice Interruptus.

22In addition, ‘race’ is implicitly implicated in the gender division between paid and unpaid labour. That division relies on a normative contrast between a domestic sphere and a sphere of paid work, associated with women and men respectively. Yet the division in the United States (and elsewhere) has always also been racialized in that domesticity has been implicitly a ‘white’ prerogative. African-Americans especially were never permitted the privilege of domesticity either as a (male) private ‘haven’ or a (female) primary or exclusive focus on nurturing one’s own kin. See Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present, New York 1985; and Evelyn Nakano Glenn, ‘From Servitude to Service Work: Historical Continuities in the Racial Division of Reproductive Labor’: Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 18, no. 1 (autumn 1992).

23In a previous draft of this paper I used the term ‘denigration’. The ironic consequence was that I unintentionally perpetrated the exact sort of harm I aimed to criticize—in the very act of describing it. ‘Denigration,’ from the Latin nigrare (to blacken), figures disparagement as blackening, a racist valuation. I am grateful to the Saint Louis University student who called my attention to this point.

24Racial disparagement can take many forms, of course, ranging from the stereotypical depiction of African-Americans as intellectually inferior, but musically and athletically gifted, to the stereotypical depiction of Asian-Americans as a ‘model minority’.

25This helps explain why the history of black liberation struggle in the United States records a pattern of oscillation between integration and separatism (or black nationalism). As with gender, it would be useful to specify the dynamics of these alternations.

26Not all versions of multiculturalism fit the model I describe here. The latter is an ideal-typical reconstruction of what I take to be the majority understanding of multiculturalism. It is also mainstream in the sense of being the version that is usually debated in mainstream public spheres. Other versions are discussed in Linda Nicholson, ‘To Be or Not To Be: Charles Taylor on The Politics of Recognition’, Constellations (forthcoming) and in Michael Warner, et al, ‘Critical Multiculturalism’, Critical Inquiry, vol. 18, no. 3 (spring 1992).

27Recall that sexuality is here assumed to be a collectivity rooted wholly in the cultural-valuational structure of society; thus, the issues here are unclouded by issues of political-economic structure, and the need is for recognition, not redistribution.

28An alternative affirmative approach is gay-rights humanism, which would privatize existing sexualities. For reasons of space, I shall not discuss it here.

29For a critical discussion of the tendency in gay-identity politics to tacitly cast sexuality in the mold of ethnicity, see Steven Epstein, ‘Gay Politics, Ethnic Identity: The Limits of Social Constructionism’, Socialist Review no. 93/94 (May-August 1987).

30The technical term for this in Jacques Derrida’s deconstructive philosophy is ‘supplement’.