Sam Klug

|

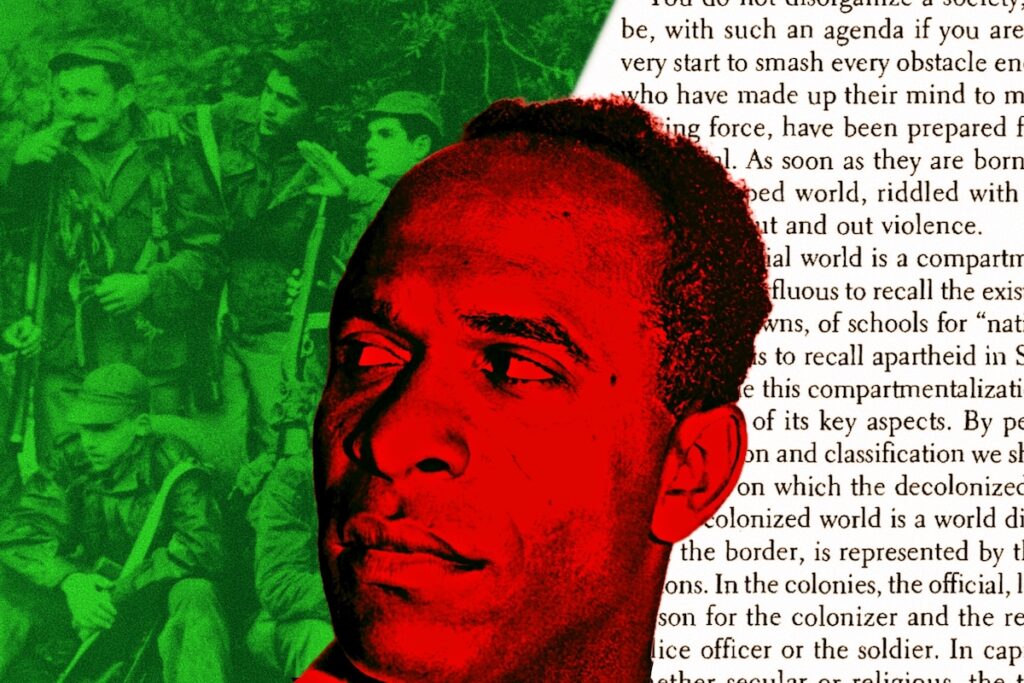

| Frantz Fanon, com soldados da FLN (à esquerda) e uma página de Os Condenados da Terra (à direita) ao fundo. Fotos: Alamy |

Adam Shatz

Farrar, Straus e Giroux, $ 32 (impresso)

Nos meses desde 7 de Outubro, muitos comentários americanos brandiram as palavras do psiquiatra martinicano e revolucionário anticolonial Frantz Fanon como prova da suposta degradação moral da esquerda. O comentarista conservador Eli Lake, escrevendo no The Free Press, de Bari Weiss, fornece um exemplo representativo. "Todo este fanonismo, tão popular na academia hoje, está a ser usado para justificar a retórica exterminacionista contra o único Estado judeu e contra os judeus em qualquer lugar", afirma Lake. Dos dois exemplos que ele cita, um é uma declaração da Associação Judaica de Estudantes de Direito da CUNY; ambos se referem apenas à afirmação de Fanon de que a opressão colonial tornou "impossível respirar".

Da mesma forma, o psicólogo Jonathan Haidt declara que o aumento do anti-semitismo nos campi universitários pode ser explicado pela popularidade da "terminologia direta de opressor/vítima, do pensador pós-colonialista Frantz Fanon". Argumentos semelhantes - quer façam referência a Fanon ou aludam de forma mais geral a aplicações de enquadramentos do colonialismo, do colonialismo dos colonos ou da descolonização a Israel-Palestina - permeiam cada vez mais as reações dominantes ao crescente movimento pela solidariedade palestina nos Estados Unidos.

Essas caricaturas refletem uma longa tradição de Fanon fomentar o medo entre conservadores e liberais americanos. Durante décadas, Fanon foi invocado como bicho-papão em debates sobre Israel-Palestina, o ativismo negro nos Estados Unidos e até mesmo a política do ensino superior. Em 2014, escrevendo no rescaldo de uma campanha de bombardeamento israelense que matou mais de 2.000 palestinos em Gaza, o falecido sociólogo e ativista da Nova Esquerda Todd Gitlin denunciou Fanon como defensor de um "tipo de maniqueísmo brutal". Em 1967, após um verão pontuado por revoltas negras em Newark e Detroit, Aristide e Vera Zolberg lamentaram a "americanização de Frantz Fanon" por parte dos seus intérpretes e admiradores do movimento Black Power. E em um discurso em Harvard em 1990, Allan Bloom - protestando contra o "radicalismo" que tomava conta dos departamentos de humanidades - descartou Fanon como “um escritor efêmero outrora promovido por Jean-Paul Sartre devido ao seu ódio assassino pelos europeus e à sua adesão ao terrorismo".

O status de bicho-papão de Fanon pouco revela sobre seu pensamento, mas revela uma tendência real em sua recepção. Mais do que qualquer outro pensador do século XX, Fanon foi lembrado e interpretado através dos seus aforismos, que são por sua vez líricos, sedutores e cativantes. "Um negro não é um homem", mas reside em uma "zona de não-ser". "A Europa é literalmente a criação do Terceiro Mundo." Ou, o mais famoso: "A descolonização é sempre um fenômeno violento".

Mas expressões isoladas são apenas "pedaços de um homem", como observa Adam Shatz, citando Gil Scott-Heron, em The Rebel's Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. Neste novo livro oportuno e envolvente - a primeira biografia completa em inglês desde a de David Macey em 2000 - Shatz restaura um senso de totalidade à vida e obra de Fanon. A busca unificadora da vida de Fanon, argumenta Shatz, foi a "desalienação" daqueles que sofriam de opressão racial e colonial - um projeto ao mesmo tempo individual e social, clínico e político. Para Fanon, conclui Shatz, esse era o objetivo final da psiquiatria como prática de liberdade.

Em um momento em que Fanon é mais uma vez profundamente mal interpretado e distorcido, The Rebel's Clinic ajuda-nos a regressar a Fanon inteiro - a plenitude do seu pensamento e prática para além dos aforismos familiares. Sobre quatro questões, em particular, Fanon fala hoje com maior vigor, e nem sempre da forma que poderíamos esperar: o lugar da violência nas lutas pela libertação; a fenomenologia da negritude e a experiência da racialização; a relação entre tradição cultural e luta política; e a natureza da ordem global liderada pelo Ocidente.

Fanon nasceu em 1925 em Fort-de-France, capital da Martinica, uma das antigas colônias francesas no Caribe. Ele morreu jovem, como tantos radicais negros do século XX - em 1961, com apenas trinta e seis anos, de leucemia. Ele veio pela primeira vez para a França como soldado, alistando-se nas Forças Francesas Livres durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial. Depois da guerra, estudou medicina e psiquiatria, mergulhando nos métodos heterodoxos de "terapia institucional" associados ao psiquiatra radical François Tosquelles no asilo de Saint-Alban. Ele veio pela primeira vez para a Argélia como médico, para prosseguir e ampliar estes métodos, em 1953 - onde acabaria por se tornar mais conhecido como um rebelde do que como um clínico.

Shatz dá ênfase especial ao trabalho de Fanon como psiquiatra, incluindo seu trabalho clínico em hospitais na França, na Argélia e na Tunísia. A profundidade e a sofisticação do tratamento deste material no livro marcam a diferença mais significativa em relação ao estudo de Macey, que, em vez disso, revela muito mais sobre a educação e o início da vida de Fanon na Martinica. Na verdade, é através desta lente psiquiátrica que Shatz aborda as duas questões que mais preocuparam os intérpretes de Fanon: as suas opiniões sobre a resistência violenta à opressão e a sua compreensão da raça.

Long before he arrived in Algeria, Fanon knew violence firsthand—both the everyday violence of a colonial order and the violence of modern war. The Algerian revolution broke out in 1954, a year after he was hired to direct the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. Fanon and his staff immediately put their clinic in the service of the revolution, to members of the National Liberation Front (FLN). This daring choice endeared Fanon to the group’s regional leadership—especially military strategist Abane Ramdane, who would guide Fanon’s path into the FLN’s inner circle. Fanon never designed FLN policy or strategy himself; initially he was a spokesman, writing articles for the FLN’s newspaper El Moudjahid, and later he would become a diplomat, representing the FLN through its diplomatic arm, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Algeria (GPRA), in the newly independent nations of Africa.

It was in this context that Fanon developed his ideas about violence, which come through most vividly in the stories he told about the revolution at it was unfolding rather than from his actions within it. These accounts—captured in the books A Dying Colonialism (1959), Toward the African Revolution (1964), and, most of all, The Wretched of the Earth (1961)—would become among the most widely read texts on decolonization ever written. “At the individual level, violence is a cleansing force,” Fanon famously writes in the first chapter of Wretched, “On Violence”—or at least, that is how most translations have rendered it. The French is “la violence désintoxique.” Shatz argues that “disintoxicating” is a more appropriate translation, suggesting that anticolonial violence is not necessarily righteous or redemptive but a psychiatric phenomenon of sorts—one that relieves the supposed “inferiority complex” imposed by the colonizer upon the colonized.

Beyond this alternative translation, though, Shatz offers a familiar reading of “On Violence” as a straightforward defense of armed struggle against colonial rule. More compelling is his discussion of Fanon’s nuanced understanding of the place of violence in liberation struggles that emerges from a reading of the rest of Wretched.

On the one hand, in his role as FLN spokesperson, Fanon did, on occasion, justify acts of violence against civilians, including Algerians. Shatz demonstrates that Fanon worked to conceal a grisly massacre of three hundred Algerian civilians who supported a rival group to the FLN, and, closer to home, helped cover up the murder of his friend Ramdane by rivals within the FLN’s leadership. Shatz sees Fanon’s role in these acts as a sort of ethical compromise—an acceptance of the demands of revolutionary discipline, but one that came with heavy psychological costs. Ramdane’s murder, Shatz argues, haunted Fanon for the rest of his life; shortly before Fanon’s own death, he confessed to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir that he felt responsible for it.

On the other hand, Fanon argued that vengeance against the European settler population in Algeria could not form the basis of a viable political strategy. “Racism, hatred, resentment, and ‘the legitimate desire for revenge’ alone cannot nurture a war of liberation,” he concludes. Animus toward the settler population or the colonial power may well be an inevitable factor in anticolonial revolt, but it was far from sufficient. “Political education of the masses,” Fanon insisted, is required to turn the “spontaneity” of the initial phase of revolt into a disalienating politics, one that creates a new universalism out of the wreckage of the old.

This view of violence is most evident in the final chapter of Wretched, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders,” where Fanon offers case histories of both Algerian and French patients he treated at the Blida-Joinville clinic and at the Charles Nicolle Hospital in Tunis. Shatz takes these stories to represent the keystone of Fanon’s pursuit of disalienation.

In one case, Fanon recounts the story of a European policeman who had tortured Algerian fighters, and who, he claimed, could “hear [their] screams even at home.” Though Fanon agreed to treat him privately, in order to keep him separate from the FLN fighters in his care at the hospital, one day this patient took a walk on the hospital grounds, where he spotted one of his former victims. Fanon “found him leaning against a tree, covered in sweat and having a panic attack” and soon noticed that his other patient, the policeman’s victim, had gone missing. “We eventually discovered him hiding in a bathroom where he was trying to commit suicide,” Fanon wrote. The Algerian had recognized the policeman and thought he had come to the hospital to arrest him.

In another case, an African freedom fighter from another independence struggle, who had placed a bomb in a café that killed ten people, was haunted by insomnia and anxiety attacks, which intensified each year on the anniversary of the bombing. This militant “never for a moment had thought of recanting,” Fanon writes. He understood his symptoms as “the price he had had to pay in his person for national independence.”

These case histories form a sobering counterpoint to Wretched’s first chapter. Fanon clearly understood the psychic wounds of colonial warfare, including the moral injury that doing violence inflicted on both anticolonial militants and French soldiers. Shatz reads Fanon as arguing that “the disintoxicating effects of violence are ephemeral at best.” If the work of decolonization could require violence, the work of disalienation required reckoning with—working through—the costs that violence incurred.

At the same time, Fanon’s thinking about anticolonial violence cannot be understood apart from his sophisticated analysis of the nature of colonial violence, which Shatz largely overlooks in The Rebel’s Clinic. He is far from alone in this elision, which often undergirds the portrait of Fanon as a prophet of violence.

Colonial violence is depicted in Fanon’s writings, especially Wretched, in two ways. First and most obvious is the brutal French war of counterinsurgency, which inflicted widespread torture and mutilation and killed hundreds of thousands of Algerians. Fanon sees the war as both a logical outcome of the colonial regime and a pathological expression of racist, colonial fears of the inherently violent “native.” “Colonized society is not simply described as a society without values,” he writes in Wretched.

The colonist is not content with stating that the colonized world has lost its values or worse never possessed any. The “native” is declared impervious to ethics, representing not only the absence of values but also the negation of values. He is, dare we say it, the enemy of values. In other words, absolute evil. A corrosive element, destroying everything within his reach, a corrupting element, distorting everything which involves aesthetics or morals, an agent of malevolent powers, an unconscious and incurable instrument of blind forces.

Daí a violência brutal e feroz desencadeada sobre os "nativos" que resistem.

But beyond the violence of war, there was also the less discrete, more quotidian violence of colonial rule itself, which Fanon had experienced in different forms in Martinique and Algeria—the simultaneously psychic and somatic violence of racialized regimes of interpersonal harm and economic inequality that colonial society imposed. The colonial world is a “Manichaean world,” Fanon explains—a “world cut in two.” It is “a world with no space, people are piled one on top of the other, the shacks squeezed tightly together. The colonized’s sector is a famished sector, hungry for bread, meat, shoes, coal, and light.” In it, “you are born anywhere, anyhow. You die anywhere, from anything.” The sinews of the colonial order, moreover, linked this everyday violence to the spectacular violence of colonial warfare, and the denial of humanity that accompanied it: “Sometimes this Manichaeanism reaches its logical conclusion and dehumanizes the colonized subject,” Fanon explains. “In plain talk, he is reduced to the state of an animal.”

Fanon’s dictum that “decolonization is always a violent phenomenon” must be understood in this context. This most cherry-picked line of Fanon’s writings represents not so much a strategic injunction, and still less a blanket justification for killing, as an acknowledgment of the scale of transformation—from the personal to the structural—that decolonization entailed. As philosopher Lewis R. Gordon observes in What Fanon Said (2015), Fanon’s work emerged from the recognition that “colonialism’s victory would be continued violence; the colonized’s victory would be, to the colonial forces, violence incarnate.”

A onetime playwright, Fanon was sensitive to the dramaturgy of struggle. In his landmark Conscripts of Modernity (2004), anthropologist David Scott counterposes the “romance” of decolonization long associated with the work of Fanon and other anticolonial writers to the “tragedy” evident in the second edition of C. L. R. James’s study of Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins (1963). As Scott reads them, James’s additions to the original 1938 text stressed the “irreconcilable dissonance between Toussaint’s expectations for freedom and the conditions in which he sought to realize them, between the utopia of his desire and the finitude of his concrete circumstances.” The same could be said of Fanon. To sever ties with France, to reconstitute Algerian society, to forge out of the ruins of European humanism a “new man”—all represented wrenching, violent transformations that imposed significant costs on the relationships, identities, and forms of life of those involved in the struggle, not least Fanon himself.

Ler o trabalho de Fanon desta forma deixa em aberto muitas das questões de estratégia que "Sobre a Violência" muitas vezes se presume responder. O trabalho de Fanon serve como um corretivo estimulante para a imaginação liberal contemporânea, que tanto privilegia as ordens políticas existentes como apresenta um modelo extremamente circunscrito de desobediência civil não violenta como a única forma de resistência política moralmente aceitável ou estrategicamente viável. Em vez de resolver a questão dos meios e dos fins nas lutas anti-racistas e anticoloniais, um reconhecimento fanoniano da violência inerente à derrubada de uma ordem mundial racial-colonial abre o terreno para uma conversa mais produtiva sobre eles.

Além dos debates sobre a violência anticolonial, Fanon é mais invocado hoje em discussões sobre racialização e a "experiência vivida da negritude". Aqui, também, Shatz enfatiza as dimensões psiquiátricas do pensamento de Fanon - e apresenta uma psico-história parcial do seu tema.

Fanon’s first book, Black Skin, White Masks, was published in 1952. (The text was initially rejected as Fanon’s doctoral thesis by his adviser on the faculty of medicine in Lyon.) The young Fanon, then twenty-six, plotted the psychic coordinates of a society defined by racism, especially its fears and fantasies of Black sexuality. With Black Skin, White Masks, Shatz argues, Fanon found his voice not only as a philosopher of the “lived experience of Blackness” but as a diagnostician of what historians Barbara and Karen Fields call “racecraft”—the ideologies, myths, and neuroses that “form us as racialized individuals.”

Shatz also sees the book as a critical moment in Fanon’s own Oedipal drama, reckoning as it does with not one but two of Fanon’s intellectual father figures: the Martinican poet and politician Aimé Césaire and the French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Though Fanon was deeply influenced by Sartre’s analysis of racial formation in Anti-Semite and Jew (1946), he fulminated against Sartre’s characterization of Négritude—the literary movement pioneered by Césaire and other Afro-Caribbean writers—as “the weak stage of a dialectical progression” that had to be superseded in order to achieve “the realization of the human society without race.” To Fanon, this verdict smacked of white paternalism and dismissiveness, and it came too close to the empty assertions of common humanity that pervaded French republicanism—only made more unbearable by the everyday racist humiliations Fanon experienced on the streets of Lyon.

At the same time, Fanon had his own criticisms of Négritude. He deeply admired Césaire’s idea of “Blackness as invention,” but he criticized the movement’s orientation to history. “In no way does my basic vocation have to be drawn from the past of peoples of color,” he insisted. Instead, Shatz argues, Fanon understood disalienation as aiming at freedom from the past—grounded in an existentialist insistence on the necessity of self-invention.

This reading of Black Skin, White Masks sets Shatz against Afropessimist receptions of Fanon, which have claimed him as the philosophical spokesman of an ontological—not merely phenomenological or historical—anti-Blackness. As Jesse McCarthy explores in a critical essay, the theoretical foundation of Afropessimism links “racial exceptionalism, political immutability, ‘antiblackness’ as structural antagonism, and abjection in the form of ‘social death.’” Whereas each of these concepts predate Afropessimism, their particular synthesis, in the work of figures such as Frank Wilderson III, is often premised on a selective reading of Fanon.

Above all, this Fanon is a theorist of permanent abjection. For Wilderson, Césaire’s vision of “Blackness as invention” is hopelessly naïve; instead, he writes, “Blackness is a locus of abjection to be instrumentalized on a whim.” Similarly, Wilderson takes Fanon’s account of racial interpellation in Black Skin, White Masks to expose the “ruse of analogy.” The ontological and exceptional character of Black abjection means that “there is no analogy between the suffering of Black people and those others who find themselves subjugated by unethical paradigms”—and, consequently, that the very idea of interracial solidarity is a logical impossibility.

For Fanon, though, history was not essence, much less destiny; his diagnosis and etiology of the “epidermalization” of inferiority was not a prediction of its permanence. The Rebel’s Clinic shows that Fanon, true to his existentialist inheritance, was always oriented to a future in which the degradation of Blackness might be undone—not least, through a struggle against the global colonial order, which required forging solidarities across racial, religious, and national lines.

Este é um corretivo útil para o Fanon afropessimista, mas pode facilmente cair no exagero. Fanon pode ter tido um "desejo ardente de alcançar a liberdade da história", como escreve Shatz, mas não era um voluntarista ético. No que Shatz chama de "batalha constante entre a ferida e a vontade", o exercício da vontade de Fanon derivou em parte da "descoberta de que a raça era uma construção, não uma realidade biológica", o que, argumenta Shatz, "alimentou um sentimento de otimismo sobre a nossa capacidade de superar o conflito racial." Isto é tão enganador quanto ler Fanon como um pessimista racial absoluto. Como argumenta o filósofo ganense Ato Sekyi-Otu em Dialética da experiência de Fanon (1996), o repúdio de Fanon a “um fundacionalismo reducionista racial de julgamento e conduta moral” não o tornou otimista, mas sim aberto a uma série de futuros raciais - todos de o que invariavelmente refletiria a “consequência restritiva da história colonial”. Para Fanon, conclui Sekyi-Otu, alcançar um mundo livre de hierarquia racial depende menos da “liberdade desimpedida e da decisão opcional do sujeito moral” do que da capacidade de forjar - a partir de "agentes sociais presos em uma teia emaranhada de antagonismo inegável e parentesco irônico" - um sujeito coletivo capaz de criar um novo conjunto de condições.

As complexidades da política revolucionária argelina - especialmente as suas divisões entre as forças militares do interior (o chamado “Exército das Fronteiras”) e a liderança política no exílio - moldaram as viagens literais e ideológicas de Fanon, que Shatz mapeia lindamente no terço final de Rebel’s Clinic. Ele coloca o trabalho de Fanon em conversa com pensadores e líderes políticos argelinos como Ferhat Abbas, Mouloud Feraoun, Mohammed Harbi e a colega e amiga de Fanon, Alice Cherki. O enquadramento destas figuras por Shatz como interlocutores-chave de Fanon marca outra diferença em relação à biografia de Macey de 2000, que estava mais preocupada com a relação de Fanon com o cânone da teoria francesa do pós-guerra. Também lança mais luz sobre o pensamento de Fanon sobre a relação entre a tradição cultural e a luta política, que animou os seus primeiros compromissos com a Negritude.

A central matter of debate within the FLN was the place of Islam in the revolution and in postcolonial Algeria. Shatz is wistful for the secular and pluralistic Algeria Fanon and his leftist comrades like Ramdane imagined, counterposing it to the tragedy of the Algerian civil war in the 1990s (which began after a military coup nullified an election victory by the Islamic Salvation Front, leading to eight years of violence between government forces and Islamist insurgent groups). But by confining himself to retrospective assessment, Shatz evades a full accounting of the implications of Fanon’s secularism in his own time.

Fanon was not entirely dismissive of Islam, and the clinical success he had in integrating aspects of Muslim practice in his experiments in social therapy at Blida caused him to reconsider the role of so-called “traditional culture.” In some of his writings during the revolution, most famously his chapter “Algeria Unveiled” in A Dying Colonialism, Fanon demonstrated a growing understanding that Islamic religiosity could serve as an expression of cultural rebellion in the face of French colonialism. Yet, simply as a strategic matter, Fanon consistently underestimated the power that Islam held among his adopted countrymen, including many of his fellow revolutionaries.

Political theorist Anwār Omeish further contends that Fanon held onto the common distinction between traditional and modern in Western thought, portraying the Algerian revolution as an “awakening” to a political identity that would supersede Algerians’ cultural and religious affiliations. (In this way, Fanon seems to have ironically recapitulated the perspective he had faulted Sartre for in his writing on Négritude.) Fanon’s portrayal of Algerians as traveling a road from Islam to secular anticolonial nationalism not only misrecognized the political sociology of Algerian society but also failed to reckon with a key feature of French colonialism itself. As historian Muriam Haleh Davis has shown, Islamophobia was the modality through which French racism expressed itself in Algeria; the French state framed its colonial project as an attempt to convert Muslim peasants into the “civilized” subjects of a market economy. The turn to Islam as a source of anticolonial resistance was not merely a refusal to face the future by returning to a communal tradition; it was a forthright rejection of the specific form of racialization that French colonial rule had imposed.

A “tarefa impressionante que Fanon impõe à humanidade pós-colonial nas suas comunidades nacionais específicas”, escreve Sekyi-Otu, “é nada menos do que arrancar ao Ocidente a administração monopolista da ‘condição humana’ na sua instância concreta como o projeto moderno”. Como participante numa luta revolucionária na qual era decididamente um estranho, Fanon pode ter ignorado as formas como os recursos culturais já presentes na Argélia poderiam ser mobilizados em apoio a essa tarefa. A sua experiência lembra-nos o desafio persistente de navegar pelas condições sociais locais em busca de um horizonte político universalista.

Os pensadores negros anticoloniais há muito que desenvolvem as suas análises políticas e sonhos de futuro “à escala do mundo”, como afirmou o teórico político Musab Younis - não como uma forma de replicar o olhar imperial global, mas de resistir às "fixidezes espaciais e temporais do discurso imperial." Através da narração envolvente das viagens globais e das relações internacionais de Fanon, The Rebel's Clinic sublinha que Fanon também se rebelou contra a fixação no lugar e no tempo. “Não deveria haver nenhuma tentativa de fixar o homem, já que é seu destino ser libertado”, escreveu Fanon em Black Skin, White Masks.

This orientation is also evident in Fanon’s own thinking about global order and the world-system, though Shatz largely neglects this theme. Indeed, the predicament of the postcolonial world was as much Fanon’s subject as the drama of decolonization. As he grew more invested in the politics of Pan-Africanism in 1958 and 1959, Fanon gained a greater sense of the obstacles that newly independent nations faced. Internal divisions of ethnicity, religion, and class—combined with external plays for economic and political influence by former colonial powers and the superpower of the United States—made so-called “flag independence” insufficient.

Proof of this insufficiency came in the assassination of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba—orchestrated by Belgium, carried out by internal secessionists in the mineral-rich province of Katanga, and blessed by the United States. In one of the book’s darkest moments, Shatz reveals that Fanon, who had formed a friendship with Lumumba, was informed in advance of the plot against his life by Holden Roberto, a CIA-backed Angolan leader whom Fanon had also befriended. When Lumumba was brutally murdered, with CIA approval, in January 1961, Fanon blamed himself—as he had after Ramdane’s death.

Shatz is appropriately unsparing in his criticism of Fanon’s “gullibility” about Roberto. At the same time, Lumumba’s fate speaks to Fanon’s prescience about postcolonial politics. For Fanon, the array of dangers postcolonial states faced came together in the figure of the “national bourgeoisie.” Obsessed with Western values, this class sought not true freedom for the nation but merely a seizure of class power once held by the foreigner. “For the bourgeoisie,” Fanon wrote, “nationalization signifies very precisely the transfer into indigenous hands of privileges inherited from the colonial period.” In the absence of a positive program to combat the underdevelopment created by colonialism, the leader of the new nation—backed by the national bourgeoisie—basks in the glow of history, invoking both the struggle for independence and the mythic past of cultural nationalism to justify his reign.

Shatz rightly sees in this analysis “a startling anticipation of the Mobutus and the Mugabes of the future,” lauding Fanon for his prescient critique of post-independence rulers who parlayed cultural nationalist appeals into popular legitimacy and personal riches. But this venality, for Fanon, was not only a character flaw; it was a function of their place in a hierarchical global economy. Colonialism created the conditions for the cravenness of the post-independence national bourgeoisie. As he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth:

As soon as the capitalists know, and they are obviously the first to know, that their government is preparing to decolonize, they hasten to withdraw all their capital from the colony in question. The spectacular flight of capital is one of the most constant phenomena of decolonization.

Absent a remaking of the global economic order created by colonialism, the new ruling classes had no choice but to pursue capital from whatever sources were available—opening the way for multinational corporations and international finance to exercise extraordinary power across the postcolonial world.

This sense of colonialism as a world-ordering project pervades Fanon’s analysis of anticolonial nationalism. On the one hand, because the slave trade and European colonization had precluded the free development of Third World societies, the development of “national consciousness” represented the only hope for the creation of a genuine “international consciousness.” “The building of a nation,” Fanon argued, was the counterpart to the “discovery and encouragement of universalizing values.” On the other hand, Third World nationalism would falter if it simply replicated the model of the nation-state that had first emerged in post-Westphalian Europe. The conclusion of Wretched offers a final series of admonitions, imploring leaders and intellectuals of the Third World not to “imitate Europe” or be “obsessed with catching up with Europe.”

Shatz understands these statements in a literary and philosophical register; to him they exemplify Fanon’s attempt to forge a new, truly universal humanism out of the wreckage of the false humanism of the European philosophical tradition. This existentialist reading does capture a core concern of Fanon’s thought. But it erases the fact that the conclusion of Wretched was also intervening in a conversation about how national liberation movements should orient themselves toward the European and American-led global order.

This sense of colonialism as a world-ordering project pervades Fanon’s analysis of anticolonial nationalism. On the one hand, because the slave trade and European colonization had precluded the free development of Third World societies, the development of “national consciousness” represented the only hope for the creation of a genuine “international consciousness.” “The building of a nation,” Fanon argued, was the counterpart to the “discovery and encouragement of universalizing values.” On the other hand, Third World nationalism would falter if it simply replicated the model of the nation-state that had first emerged in post-Westphalian Europe. The conclusion of Wretched offers a final series of admonitions, imploring leaders and intellectuals of the Third World not to “imitate Europe” or be “obsessed with catching up with Europe.”

Shatz understands these statements in a literary and philosophical register; to him they exemplify Fanon’s attempt to forge a new, truly universal humanism out of the wreckage of the false humanism of the European philosophical tradition. This existentialist reading does capture a core concern of Fanon’s thought. But it erases the fact that the conclusion of Wretched was also intervening in a conversation about how national liberation movements should orient themselves toward the European and American-led global order.

Um participante desta conversa foi Richard Wright, cujo Native Son foi uma das primeiras inspirações para Fanon. Na seção final de Black Power (1954), um relato da sua estada no Gana, que em breve se tornaria independente, Wright instou Kwame Nkrumah a ter cuidado com o capital ocidental, que apenas levaria Gana “da escravatura tribal à industrial, por que vinculado ao dinheiro ocidental está o controle ocidental, as ideias ocidentais”. Embora menos focado nas políticas específicas de ajuda e investimento, Fanon ecoou este sentimento em Wretched: “Não prestemos homenagem à Europa criando Estados, instituições e sociedades que nela se inspirem”. Para Fanon, a libertação para o capitalismo ocidental e o nacionalismo europeu não era de todo uma libertação. Em vez de ser uma oportunidade para mais Estados aderirem à chamada “ordem internacional liberal”, a descolonização era uma forma de revelar as suas patologias - e começar a superá-las.

À medida que a guerra avança em Gaza e na Ucrânia, as patologias desta ordem são mais visíveis do que nunca. Shatz escreve, na sua conclusão, que "o nosso mundo não é o de Fanon, mas a sua crítica ao poder e às relações internacionais mantém grande parte da sua força".

O mesmo acontece com o seu diagnóstico das formas como a violência em ação na ordem racial e colonial do mundo pode causar estragos na mente humana. Podem-se ouvir ecos da busca de Fanon pela desalienação nas palavras do poeta palestino Najwan Darwish. Em uma entrevista em Janeiro à jornalista Alexia Underwood, Darwish testemunhou a guerra colonial que se desenrola em Gaza - e os transtornos mentais que a acompanham:

Uma das verdadeiras lutas nestes tempos é não perder a cabeça, porque um dos objetivos de qualquer sistema opressivo, como o colonialismo, é enlouquecer os oprimidos. É um sistema de controle. Se tiverem sucesso, ninguém irá ouvi-lo quando você começar a gritar. Já vi isso acontecer com pessoas ao meu redor, então fiquei um pouco obcecado com isso. Quando suporto atrocidades ou as testemunho, eu me questiono e me lembro disso, e isso me traz de volta à sanidade.

Como Fanon escreveu certa vez: "A loucura é uma das maneiras que os humanos têm de perder sua liberdade".

Sam Klug é professor assistente na Loyola University Maryland e pesquisador visitante no Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History em Harvard. Ele é autor do próximo livro The Internal Colony: Race and the American Politics of Global Decolonization.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário